EVEN EIGHT MONTHS IN to the Strange Tales run of Nick Fury Agent of SHIELD, it didn't seem as if writer and editor Stan Lee really had a handle on the series. The first seven episodes had repurposed ideas lifted from the first four James Bond movies and the first couple of seasons of Man from UNCLE. Some of the blame for these slightly below average comics can be laid at Stan's door, but really, it was Kirby that was floundering.

Left to his own devices to plot the SHIELD stories, Jack Kirby drew up a storm but the ideas weren't coming together to form a cohesive whole.

Strange Tales 142 (Mar 1966) was the last issue of the title to go on sale in 1965 (9th Dec), with Jack Kirby returning to provide full pencils for Micky (Esposito) Demeo's inks. The episode kicks off with bombast and gunfire as Fury and his SHIELD technicians test a peculiar-looking robo-gunman. The contraption goes haywire until one of the tech guys literally pulls the plug. It's a great action opening, but it has nothing to do with the rest of the story - exactly the kind of thing Kirby does when he doesn't have a solid story idea.

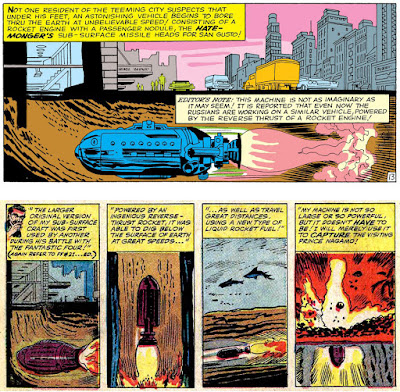

The real plot kicks off when SHIELD's ESP division reports that powerful mind-reader Mentallo has penetrated the secret lair of The Fixer (a kind of bargain-basement Mad Thinker) and the two have formed a sinister partnership. When it comes time for the villains to attack SHIELD, they arrive in a subterranean tank not dissimilar to the vehicle used by the Hate Monger in Fantastic Four 21 (Dec 1963, which also starred Nick Fury) and the mole machine used by The Rabble Rouser in Strange Tales 119 (Apr 1964).

During the scene, The Fixer explains that he's had help building his burrowing vehicle from an organisation called THEM, though he doesn't elaborate further. Does this mean that The Hate Monger and the Rabble Rouser (two quite similar villains) also had help from THEM? Or was Marvel just lazily recycling old ideas? You decide ...

Eluding SHIELD's defences, the evil pair are soon inside SHIELD's nerve centre and take on Fury and his security detail. They disable the defending soldiers with "Element Z", a paralysing agent, and capture Fury, planting a mind-control mask over his face.

It's okay as action comic stories go, but I can't help feeling that if Stan had more of a hand in plotting this, he'd have a bit more actual story going on. What is kind of interesting is that the plot crosses over slightly with Tales of Suspense 75 (Mar 1966) which, for the Captain America strip, was a bit of a new beginning, with Kirby back on full pencils after the lacklustre stories drawn by George Tuska, featuring the slightly tedious Sleeper story-arc.

Strange Tales 143 (Apr 1966) is a bit better, storywise. This time the art is credited to Jack Kirby with an assist from Howard Purcell, and inks by Mike Esposito again. The plotting seems a bit more detailed, with SHIELD essentially having used Fury as bait to draw The Fixer and Mentallo into a trap. With the head of SHIELD strapped to an H-Bomb, the baddies think they can force SHIELD to obey their orders, but of course it doesn't work out that way. Fury is able to send a mental message to the ESP Division, and Dum-Dum Dugan and the other ex-Howlers attack, as The Fixer and Mentallo are disabled with a psychic attack from the ESP team, and disintegrate the H-Bomb with Tony Stark's Neutralizer weapon.

It's a satisfying end to the three-part story, but the pages not fully-pencilled by Kirby are a little bland, despite Howard Purcell's pedigree as a veteran penciller with 25 years experience. The next issue would continue with the same creative team and a new villain, The Druid.

Less than a year later, Purcell landing his first cover assignment, with All-American Comics 25 (Apr 1941), drawing lead character Green Lantern. The same month, Purcell began pencilling Red, White and Blue in All-American Comics 25. The following month he picked up the art assignment from Sargon the Sorcerer in All-American Comics 25 onwards and Lando, Man of Magic in Word's Best (Finest) Comics from issue 1 (Spr 1941).

Yet, just as quickly, these assignments faded away and by the beginning of 1944, Purcell was drawing just The Gay Ghost for DC's Sensation Comics. Purcell's comics career picked up after WW2, and in 1947, he became the main artist on DC's Green Lantern, as well as regularly drawing Hop Harrigan in All-American Comics and Johnny Peril in All-Star Comics. In 1949 he was the main artist for Mr District Attorney until 1957. From there Purcell was once again a jobbing artist, working for the DC anthology comics, House of Secrets, House of Mystery, Tales of the Unexpected and My Greatest Adventure, until 1964, when he took over on Sea Devils.

Purcell's work on SHIELD in Strange Tales was a bit of an anomaly, because straight after he continued with his regular assignment on Sea Devils for DC until 1967. In 1968, Purcell drew romance stories for Young Romance and Heart Throbs, but at the end of that year, he made a brief return to Marvel and drew the first Black Knight solo story in Marvel Superheroes 17 (Nov 1968) along with a couple of Watcher back-up tales in Silver Surfer.

Then it was back to DC for intermittent assignments during the early 1970s on Adventure, Detective and Brave and the Bold. By the mid-1970s, Purcell had pretty much retired. He died on 24th April 1981.

The story starts off with a weird magical ceremony, except that it doesn't seem to be magic at all, just the same old advanced technology. Quite what The Druid's deal is, I'm not sure, but he sure seems to have a grudge against SHIELD. Using "mystical rites combined with modern, sinister science" the Druid and his followers launch a deadly Satan Egg which is programmed to find Colonel Fury and destroy him.

The whole "magic combined with science" schtick does seem to be a bit of a hobby-horse for Jack Kirby. He's used it over and over again, most notably with Fantastic Four foe Dr Doom, and it's a great idea ... but for me it's never been wholly successful. As time went by, the magic component of Doom's abilities was dropped and Kirby moved him more towards super-science - technology that couldn't be explained by our real-world Newtonian physics. That's also my take on the technology in Kirby's Fourth World stories and the follow-up The Eternals. There doesn't appear to be any magic involved in what The Druid does either, unless he's just using the mystic trappings to fool his followers - though that isn't made apparent in the script.

More entertaining in this story is the introduction of boy-scout SHIELD agent Jasper Sitwell. Despite his being subverted as a sleeper Hydra agent in the recent Marvel Movies, I always like the Sitwell character and thought he was more than just a comic foil for Fury and the other agents. Stan treated the character with respect and made him a highly capable agent, despite the buffoonish veneer. There has been some speculation that penciller Howard Purcell based Jasper Sitwell on Marvel editor Roy Thomas, but I can't see much resemblance.

There would be more Jasper Sitwell in Strange Tales 145 (Jun 1966). As Fury is drawn into a final confrontation with The Druid, the wily technical wizard forces Fury into hand-to-hand combat. Fury appears to fall into The Druid's trap, but is in reality playing for time to give Sitwell the opportunity to take out The Druid's army of henchmen. The Druid is defeated and unmasked, though SHIELD are unable to identify him. A pretty unmemorable villain, The Druid does show up in some later 1970s issues of Captain America.

A few story points are explained during this episode. There are further references to Them. The Fixer (remember him?) is interrogated by Fury and reveals that he works for THEM, but reveals there is no connection between THEM and The Druid. Stan also includes a caption box to explain that The Druid's "outward trappings suggest a cult of black magic, to impress the unthinking masses, it is a magic founded on deception." So that clears that up, then.

The art is once more Don Heck pencils over Jack Kirby plot and layouts, with Mike Esposito again on inks. Esposito's inks are especially unsuited to Heck's fine pencils and the artwork for this issue has the bland look of shop-created comic strip art, due to the diversity of art styles that just fail to mesh. All of which contributed to the feeling that Stan and Jack almost regretted ever starting this series and were struggling to get some life and energy into it.

There's also mention of the events in the Captain America strip in Suspense 78 (May 1966), which happen between Strange Tales 145 and 146 and should probably be read before moving on to the next Nick Fury adventure. But briefly, Fury takes the mini brain he discovered on The Fixer's person back in ST145 to Cap to ask if he's come across anything like it and if he's heard of Them. The pair are attacked by a battledroid and defeat it. That's pretty much it.

On sale the same day as Tales of Suspense 78 (10th March 1966), Strange Tales 146 featured Them as a full-blown enemy of SHIELD. The story also introduces the outfit called AIM (Advanced Idea Mechanics) who step forward to offer technology to SHIELD after Tony Stark's factories are shut down and Stark himself is under congressional investigation.

THEM have hijacked SHIELD's LMD technology and have crafted mindless warrior androids designed to fight in any environment. We get to see the underwater version attack a SHIELD swamp buggy in the opening sequence of the story, though they're repelled and SHIELD are able to track them to THEM's HQ.

We're also introduced to Count Royale, a representative of A.I.M., who wants to offer advanced technology to SHIELD. He appears to have the endorsement of some senior military types, though we'll learn later in the story that it seems as though A.I.M. are playing both ends against the middle and supplying advanced weapons to both SHIELD and THEM.

The art is still Don Heck pencils over minimal layouts from Kirby and Esposito inks. The art has much more of a Heck look to it, especially apparent in the design of the THEM uniforms, which definitely have a Heck look about them.

The plot does start to get a little bit richer in Strange Tales 147 (Aug 1966), as the full extent of Count Royale's plan is revealed. In a scene at the beginning of the episode Royale expresses his concerns to the US military generals that A.I.M. feels Fury is not the right kind of person to be leading SHIELD. We then see A.I.M. stage an invasion of SHIELD's barbershop entrance, taking the guarding agents hostage. Fury is forced into a reckless personal rescue mission, reinforcing Royale's claims that he's too reckless to lead such an important organisation. Though Fury and his team defeat the A.I.M. invaders, he plays directly into the hands of Royale and as the episode comes to end, realises that his future as Head of SHIELD is now in the balance.

As much as I thought Mike Esposito's inks were ill-suited to the pencils of Don Heck, I thought that this issue's art was even less attractive than the preceding issues. Was Esposito especially rushed on this issue? No, he didn't even ink it. Despite the credits naming "Mickey Demeo" as the embellishers, turns out the art was inked by Dick Ayers - a fine enough artists in his own right, but probably the one inker I'd think of as even less suited to Heck's delicate pencil work than Esposito.

It all starts coming to a head in Strange Tales 148 (Sep 1966). After an assassination attempt by A.I.M. that kills an LMD instead of Fury, the head of SHIELD realises that they're under surveillance and plans to thwart A.I.M.'s attempt to discredit him. His nerves apparently frayed by the pressure he's under, Fury snaps at the loyal Jasper Sitwell and tells him to stay out of his hair.

Later, when Fury is summoned before a hearing to determine his fitness for office, he appears to lose his temper again and makes to physically attack Count Royale. But when Sitwell is called to the stand, he begins by saying that there's not a man he hates more than Fury. But of course it's a ruse, and Sitwell reverses the direction of his testimony and Fury leaps out a window to escape.

This is one of the few early Marvel stories that is openly credited to Jack Kirby - both plot and script. The "voice" doesn't sound so very different to that of Stan Lee, so I have to wonder just how much editing Stan did before this issue went to press. That said, there's some inconsistencies and plain old plotting errors that I'd have to point out.

Firstly, there's a very confusing sequence early in the story where a technician demonstrated a "transparency ray" that works like an x-ray machine that needs no film of screen for the effects to be visible. The big frame in the middle of the page makes it look like Fury's firing the ray - the arm holding the raygun has a green sleeve, just like the suit Fury's wearing. This makes it look like Fury's firing the ray at the technician.

And secondly, why did we need to go through the subterfuge with Sitwell pretending to hate Fury for a minor telling off? It's not like Sitwell's reversing his testimony on the witness stand helped Fury escape. And indeed, Fury's escaping just plays more into the hands of Count Royale. So it comes across as bad plotting. Where was Editor Stan Lee when he was needed? (Oh yes, on holiday, as mentioned in the issue's credits.) But despite these minor carps, it's still a fun issue and quite satisfying to know that Fury and Sitwell had a plan all along. More of that unfolds the following month.

Strange Tales 149 (Oct 1966) is headlined as "The End of A.I.M." - and it just might look that way. After a three page sequence where A.I.M. steal an LMD of Fury, but are in reality kidnapping and armed, dangerous and very real Nick Fury, the action switches back to the SHIELD Helicarrier. In the confusion, Count Royale sneaks away to rejoin his A.I.M. co-conspirators, but fails to notice Sitwell tagging him with a tracking device ... with a pea-shooter.

Sitwell is able to follow Royale to a hidden lair inside a mountain, but no sooner does Royale enter than the entire mountain explodes. Alerted that another player in the game must've destroyed A.I.M.'s headquarters, Fury searches the paraphernalia captured by SHIELD the last time they encountered Hydra. Is Fury's hunch correct ... are Hydra behind, THEM, A.I.M. and possible even The Secret Empire?

This episode of SHIELD marked a major re-jig in creative personnel. Stan took a step back and turned over scripting to neophyte Denny O'Neil, at least for this one issue. And while Kirby was still on layouts, the full art was provided by long-time ACG artist Ogden Whitney. ACG was going out of business at this time and Whitney presumably needed work fast. In my view, he was spectacularly unsuited to Marvel superhero work and though he does a professional and tidy job, it lacks the pizzaz that the regular Marvel artists could muster.

Just as suddenly, Whitney jumped ship to Columbia, a comic book offshoot of the McNaught and the Frank Jay Markey newspaper syndicates, where he took up residence as chief artist on Columbia's launch title Big Shot Comics, co-creating Skyman with another DC superstar Gardner Fox. He would also draw Rocky Ryan for the same comic, and would continue with Columbia until the end of the 1940s.

But in January 1943, he joined the US Army, driving an army truck for a while after basic training. He soon found himself in the same art department as fellow comics artist Fred Guardineer, drawing signs and posters. He also found time to continue with his comics assignments for Columbia. Later in the war, he served in the Adjutant General's office in the Philippines. He was honorably discharged in early 1946 with the rank of Master Sergeant, and returned to his mother's home in Woodside, Queens, NYC.

In the post-war years, Whitney continued to contribute art to the Columbia titles, but also began selling to Magazine Enterprises, which was founded by former Columbia editor Vin Sullivan. Whitney would provide covers and internal strips for A1 (teen humour), Manhunt (crime) and several other titles. At the beginning of 1950, Whitney did a few jobs for Ziff-Davis, pencilling and inking stories for Amazing Adventures, Famous Stars and Kid Cowboy. But by The spring of 1950, he began his long-term relationship with American Comics Group (ACG), when he drew a strip for Lovelorn 5 (Apr-May 1950) for long-serving ACG editor Richard Hughes. Very quickly Whitney was drawing war, westerns, romance and mystery for ACG, but still found time to pencil and ink strips for Quality, Magazine Enterprises and, for a brief period in 1952, Atlas/Marvel.

Quality went out of business in 1956, leaving Whitney more and more reliant on his ACG account. Not that Whitney had much to worry about. As a favourite of editor Hughes, Whitney was drawing one or two stories apiece for the main ACG mystery titles Forbidden Worlds and Adventures into the Unknown and quite a few of the covers. Hughes would add Unknown Worlds in the summer of 1960, so Whitney had three regular magazines that featured his art. But in the 73rd issue of Forbidden Worlds, Whitney drew a throwaway comedy character from a Richard Hughes script, Herbie. Completely unaware they'd just started a cult, both turned their attention back to the innocuous ACG trademark mystery titles. It would be a year and a half before Herbie appeared again in Forbidden Worlds 94 (Mar 1961). Readers clearly responded, because Herbie went on to turn up in Forbidden Worlds 110, 114 and 116, then graduated to his own title in April 1964.

As the 1960s drew to a close, ACG floundered and went out of business. Richard Hughes went on to write a few scripts Jimmy Olsen and Hawkman at DC Comics and Ogden Whitney had to look elsewhere for work. He sold some art to Tower Comics, then did some work on Two Gun Kid and Millie the Model for Stan Lee at Marvel around 1967-1968.

MAD Magazine editor Ferry de Fuccio was probably one of the last comics people to see Whitney alive. In a letter to a friend he described visiting Whitney at "40 Park Avenue South ... Naturally, I gushed about Whitney's Golden Age work when I visited his apartment. His wife, Anne, was quite lovely and refined but Whitney wasn't anything like the svelte characters he used to draw. Fat and obviously addicted to liquor ... Anne seemed troubled by her husband's state. She supported the family with her private secretary job in the area of the Empire State Building. Richard E. Hughes, editor at American Comics Group, was especially helpful to 'old-timers' [and] gave Whitney work, though Ogden seemed absorbed in trying storyboard continuity samples to crack the advertising field. I saw him working on the special pads imprinted with rows of blank TV screen. He couldn't qualify. ... I passed Whitney's apartment house [circa 1972-1973] and asked the doorman: 'Does Ogden Whitney still live here?' The doorman spoke in a hush, 'No! His wife died and his condition became extremely irrational. He was finally evicted — carried bodily — from his apartment.'"

Pulp historian David Saunders reported that Ogden Whitney died at the age of 56 at Saint Barnabas Psychiatric Hospital in the Bronx on 13 August, 1975.

The story opens with Fury testing a new weapon called the Overkill Horn. SHIELD are speculating that someone else has a similar weapon and it's come as no surprise to any reader just who that other party might be. Then, when Fury is invited to a hedonistic party by international playboy Don Caballero, he astonishes his SHIELD partners by accepting the invitation. It's doubtful that Caballero's true identity will surprise anyone, either.

What stands out most about this episode of SHIELD is just how good Buscema's drawing is compared to the revolving roster of artists that has lead up to this point. His skill with characterful faces and action figurework is superb, and it's a real shame that he didn't stay on SHIELD. But if he had, then we probably wouldn't have had the incredible work of the artist who would arrive with the following issue of Strange Tales.

In the meantime, John Buscema would go on to draw three fill-issues of the Hulk series in Tales to Astonish before getting the regular gig as pencil artist on The Avengers ... a series he would draw for the next 30 issues or so, as well as branching out as the main artist on The Sub-Mariner and The Silver Surfer during the same period.

Overall, this early run of SHIELD tales feels a little unsatisfactory, but I can't make up my mind whether this is because I now know how good the subsequent run - written and drawn by Jim Steranko - would be. On balance, that's probably not the case, because I wasn't mad about these comics at the time, either.

At some point in the future, I will take a look at Steranko's sublime run on SHIELD, a job that will not seem like a chore at all.

Next: Marvel Bullpen Bulletins

Left to his own devices to plot the SHIELD stories, Jack Kirby drew up a storm but the ideas weren't coming together to form a cohesive whole.

Strange Tales 142 (Mar 1966) was the last issue of the title to go on sale in 1965 (9th Dec), with Jack Kirby returning to provide full pencils for Micky (Esposito) Demeo's inks. The episode kicks off with bombast and gunfire as Fury and his SHIELD technicians test a peculiar-looking robo-gunman. The contraption goes haywire until one of the tech guys literally pulls the plug. It's a great action opening, but it has nothing to do with the rest of the story - exactly the kind of thing Kirby does when he doesn't have a solid story idea.

The real plot kicks off when SHIELD's ESP division reports that powerful mind-reader Mentallo has penetrated the secret lair of The Fixer (a kind of bargain-basement Mad Thinker) and the two have formed a sinister partnership. When it comes time for the villains to attack SHIELD, they arrive in a subterranean tank not dissimilar to the vehicle used by the Hate Monger in Fantastic Four 21 (Dec 1963, which also starred Nick Fury) and the mole machine used by The Rabble Rouser in Strange Tales 119 (Apr 1964).

During the scene, The Fixer explains that he's had help building his burrowing vehicle from an organisation called THEM, though he doesn't elaborate further. Does this mean that The Hate Monger and the Rabble Rouser (two quite similar villains) also had help from THEM? Or was Marvel just lazily recycling old ideas? You decide ...

Eluding SHIELD's defences, the evil pair are soon inside SHIELD's nerve centre and take on Fury and his security detail. They disable the defending soldiers with "Element Z", a paralysing agent, and capture Fury, planting a mind-control mask over his face.

It's okay as action comic stories go, but I can't help feeling that if Stan had more of a hand in plotting this, he'd have a bit more actual story going on. What is kind of interesting is that the plot crosses over slightly with Tales of Suspense 75 (Mar 1966) which, for the Captain America strip, was a bit of a new beginning, with Kirby back on full pencils after the lacklustre stories drawn by George Tuska, featuring the slightly tedious Sleeper story-arc.

|

| It looks a lot to me like Jack Kirby was doing just the loosest layouts for Strange Tales 143, except for the amazing full-page drawing of Tony Stark's Neutralizer cannon on page 3. |

It's a satisfying end to the three-part story, but the pages not fully-pencilled by Kirby are a little bland, despite Howard Purcell's pedigree as a veteran penciller with 25 years experience. The next issue would continue with the same creative team and a new villain, The Druid.

WHO THE HECK IS HOWARD PURCELL?

Howard Purcell was born on 10 November 1918. Not a great deal has been documented about his early life. Little is known of his family, but we do know that he attended art classes at the The Art Students League of New York, a school that offers tuition to people from all walks of life at affordable prices. For a while he worked as an animator at the New York City studios, but by 1940 he was freelancing for DC Comics. His very first job was a regular assignment pencilling the Mark Lansing back-up feature from Adventure Comics 53 (Aug 1940) onwards. |

| Howard Purcell established himself very quickly at DC Comics during the early 1940s, and was soon drawing several back-up strips before graduating to one of DC's star features with Green Lantern. |

|

| Purcell enjoyed a long run as artist on DC's hit series Mr District Attorney, based on the successful radio and tv series of the late 1940s and early 1950s. |

|

| Purcell flirted with superhero comics during the early 1960s, but didn't pursue that course, appearing to prefer adventure titles like Sea Devils and DC's sci-fi and mystery titles. |

|

| Howard Purcell: 10th Nov 1918 - 24th Apr 1981 |

AND NOW, BACK TO AGENTS OF SHIELD

Howard Purcell would contribute pencil art for one more episode of SHIELD over Jack Kirby layouts in the following month's Strange Tales, issue 144 (May 1966).The story starts off with a weird magical ceremony, except that it doesn't seem to be magic at all, just the same old advanced technology. Quite what The Druid's deal is, I'm not sure, but he sure seems to have a grudge against SHIELD. Using "mystical rites combined with modern, sinister science" the Druid and his followers launch a deadly Satan Egg which is programmed to find Colonel Fury and destroy him.

The whole "magic combined with science" schtick does seem to be a bit of a hobby-horse for Jack Kirby. He's used it over and over again, most notably with Fantastic Four foe Dr Doom, and it's a great idea ... but for me it's never been wholly successful. As time went by, the magic component of Doom's abilities was dropped and Kirby moved him more towards super-science - technology that couldn't be explained by our real-world Newtonian physics. That's also my take on the technology in Kirby's Fourth World stories and the follow-up The Eternals. There doesn't appear to be any magic involved in what The Druid does either, unless he's just using the mystic trappings to fool his followers - though that isn't made apparent in the script.

More entertaining in this story is the introduction of boy-scout SHIELD agent Jasper Sitwell. Despite his being subverted as a sleeper Hydra agent in the recent Marvel Movies, I always like the Sitwell character and thought he was more than just a comic foil for Fury and the other agents. Stan treated the character with respect and made him a highly capable agent, despite the buffoonish veneer. There has been some speculation that penciller Howard Purcell based Jasper Sitwell on Marvel editor Roy Thomas, but I can't see much resemblance.

There would be more Jasper Sitwell in Strange Tales 145 (Jun 1966). As Fury is drawn into a final confrontation with The Druid, the wily technical wizard forces Fury into hand-to-hand combat. Fury appears to fall into The Druid's trap, but is in reality playing for time to give Sitwell the opportunity to take out The Druid's army of henchmen. The Druid is defeated and unmasked, though SHIELD are unable to identify him. A pretty unmemorable villain, The Druid does show up in some later 1970s issues of Captain America.

A few story points are explained during this episode. There are further references to Them. The Fixer (remember him?) is interrogated by Fury and reveals that he works for THEM, but reveals there is no connection between THEM and The Druid. Stan also includes a caption box to explain that The Druid's "outward trappings suggest a cult of black magic, to impress the unthinking masses, it is a magic founded on deception." So that clears that up, then.

The art is once more Don Heck pencils over Jack Kirby plot and layouts, with Mike Esposito again on inks. Esposito's inks are especially unsuited to Heck's fine pencils and the artwork for this issue has the bland look of shop-created comic strip art, due to the diversity of art styles that just fail to mesh. All of which contributed to the feeling that Stan and Jack almost regretted ever starting this series and were struggling to get some life and energy into it.

There's also mention of the events in the Captain America strip in Suspense 78 (May 1966), which happen between Strange Tales 145 and 146 and should probably be read before moving on to the next Nick Fury adventure. But briefly, Fury takes the mini brain he discovered on The Fixer's person back in ST145 to Cap to ask if he's come across anything like it and if he's heard of Them. The pair are attacked by a battledroid and defeat it. That's pretty much it.

On sale the same day as Tales of Suspense 78 (10th March 1966), Strange Tales 146 featured Them as a full-blown enemy of SHIELD. The story also introduces the outfit called AIM (Advanced Idea Mechanics) who step forward to offer technology to SHIELD after Tony Stark's factories are shut down and Stark himself is under congressional investigation.

THEM have hijacked SHIELD's LMD technology and have crafted mindless warrior androids designed to fight in any environment. We get to see the underwater version attack a SHIELD swamp buggy in the opening sequence of the story, though they're repelled and SHIELD are able to track them to THEM's HQ.

We're also introduced to Count Royale, a representative of A.I.M., who wants to offer advanced technology to SHIELD. He appears to have the endorsement of some senior military types, though we'll learn later in the story that it seems as though A.I.M. are playing both ends against the middle and supplying advanced weapons to both SHIELD and THEM.

The art is still Don Heck pencils over minimal layouts from Kirby and Esposito inks. The art has much more of a Heck look to it, especially apparent in the design of the THEM uniforms, which definitely have a Heck look about them.

The plot does start to get a little bit richer in Strange Tales 147 (Aug 1966), as the full extent of Count Royale's plan is revealed. In a scene at the beginning of the episode Royale expresses his concerns to the US military generals that A.I.M. feels Fury is not the right kind of person to be leading SHIELD. We then see A.I.M. stage an invasion of SHIELD's barbershop entrance, taking the guarding agents hostage. Fury is forced into a reckless personal rescue mission, reinforcing Royale's claims that he's too reckless to lead such an important organisation. Though Fury and his team defeat the A.I.M. invaders, he plays directly into the hands of Royale and as the episode comes to end, realises that his future as Head of SHIELD is now in the balance.

As much as I thought Mike Esposito's inks were ill-suited to the pencils of Don Heck, I thought that this issue's art was even less attractive than the preceding issues. Was Esposito especially rushed on this issue? No, he didn't even ink it. Despite the credits naming "Mickey Demeo" as the embellishers, turns out the art was inked by Dick Ayers - a fine enough artists in his own right, but probably the one inker I'd think of as even less suited to Heck's delicate pencil work than Esposito.

It all starts coming to a head in Strange Tales 148 (Sep 1966). After an assassination attempt by A.I.M. that kills an LMD instead of Fury, the head of SHIELD realises that they're under surveillance and plans to thwart A.I.M.'s attempt to discredit him. His nerves apparently frayed by the pressure he's under, Fury snaps at the loyal Jasper Sitwell and tells him to stay out of his hair.

Later, when Fury is summoned before a hearing to determine his fitness for office, he appears to lose his temper again and makes to physically attack Count Royale. But when Sitwell is called to the stand, he begins by saying that there's not a man he hates more than Fury. But of course it's a ruse, and Sitwell reverses the direction of his testimony and Fury leaps out a window to escape.

This is one of the few early Marvel stories that is openly credited to Jack Kirby - both plot and script. The "voice" doesn't sound so very different to that of Stan Lee, so I have to wonder just how much editing Stan did before this issue went to press. That said, there's some inconsistencies and plain old plotting errors that I'd have to point out.

Firstly, there's a very confusing sequence early in the story where a technician demonstrated a "transparency ray" that works like an x-ray machine that needs no film of screen for the effects to be visible. The big frame in the middle of the page makes it look like Fury's firing the ray - the arm holding the raygun has a green sleeve, just like the suit Fury's wearing. This makes it look like Fury's firing the ray at the technician.

And secondly, why did we need to go through the subterfuge with Sitwell pretending to hate Fury for a minor telling off? It's not like Sitwell's reversing his testimony on the witness stand helped Fury escape. And indeed, Fury's escaping just plays more into the hands of Count Royale. So it comes across as bad plotting. Where was Editor Stan Lee when he was needed? (Oh yes, on holiday, as mentioned in the issue's credits.) But despite these minor carps, it's still a fun issue and quite satisfying to know that Fury and Sitwell had a plan all along. More of that unfolds the following month.

Strange Tales 149 (Oct 1966) is headlined as "The End of A.I.M." - and it just might look that way. After a three page sequence where A.I.M. steal an LMD of Fury, but are in reality kidnapping and armed, dangerous and very real Nick Fury, the action switches back to the SHIELD Helicarrier. In the confusion, Count Royale sneaks away to rejoin his A.I.M. co-conspirators, but fails to notice Sitwell tagging him with a tracking device ... with a pea-shooter.

Sitwell is able to follow Royale to a hidden lair inside a mountain, but no sooner does Royale enter than the entire mountain explodes. Alerted that another player in the game must've destroyed A.I.M.'s headquarters, Fury searches the paraphernalia captured by SHIELD the last time they encountered Hydra. Is Fury's hunch correct ... are Hydra behind, THEM, A.I.M. and possible even The Secret Empire?

This episode of SHIELD marked a major re-jig in creative personnel. Stan took a step back and turned over scripting to neophyte Denny O'Neil, at least for this one issue. And while Kirby was still on layouts, the full art was provided by long-time ACG artist Ogden Whitney. ACG was going out of business at this time and Whitney presumably needed work fast. In my view, he was spectacularly unsuited to Marvel superhero work and though he does a professional and tidy job, it lacks the pizzaz that the regular Marvel artists could muster.

WHO THE HECK IS OGDEN WHITNEY?

John Ogden Whitney was born in 1918, in Stoneham, Massachusetts, to father Ethan and mother Alberta. Little has been recorded about his early life. In 1932, Whitney's father died, so the Whitney children - Ethan, Helen and Ogden then aged 17 - took jobs to support the family. After working in a print shop for a while, Ogden landed work with DC Comics, drawing his first strip, a Cotton Carver story "The Land of Thule" for Adventure Comics 41 (Aug 1939). Whitney only stayed with DC for few months, working exclusively on Adventure Comics. For the last two months of his tenure, he also drew the Adventure lead feature Sandman, taking over from incumbent penciller and then-DC-superstar Craig Fessell. |

| Despite only working for National Comics for a few months, Ogden Whitney rose from jobbing artist on backup strips to drawing the star feature in Adventure Comics, Sandman. |

But in January 1943, he joined the US Army, driving an army truck for a while after basic training. He soon found himself in the same art department as fellow comics artist Fred Guardineer, drawing signs and posters. He also found time to continue with his comics assignments for Columbia. Later in the war, he served in the Adjutant General's office in the Philippines. He was honorably discharged in early 1946 with the rank of Master Sergeant, and returned to his mother's home in Woodside, Queens, NYC.

|

| Whitney also found work at Magazine Enterprises on a variety of genres from horror to romance and humour. |

Quality went out of business in 1956, leaving Whitney more and more reliant on his ACG account. Not that Whitney had much to worry about. As a favourite of editor Hughes, Whitney was drawing one or two stories apiece for the main ACG mystery titles Forbidden Worlds and Adventures into the Unknown and quite a few of the covers. Hughes would add Unknown Worlds in the summer of 1960, so Whitney had three regular magazines that featured his art. But in the 73rd issue of Forbidden Worlds, Whitney drew a throwaway comedy character from a Richard Hughes script, Herbie. Completely unaware they'd just started a cult, both turned their attention back to the innocuous ACG trademark mystery titles. It would be a year and a half before Herbie appeared again in Forbidden Worlds 94 (Mar 1961). Readers clearly responded, because Herbie went on to turn up in Forbidden Worlds 110, 114 and 116, then graduated to his own title in April 1964.

|

| There's not a comic character stranger than Herbie. It really wasn't my cup of tea, but the character enjoyed (and still has) quite a fervant following. |

|

| At the tail end of his career, Ogden Whitney returned to Marvel to draw a few stories. I do wonder why he never tried DC Comics again. |

|

| John Ogden Whitney: 1918 -13 Aug 1955 |

... AND BACK TO SHIELD

With Strange Tales 150 (Nov 1966), Stan Lee was back on scripting duty, with trusty Jack Kirby on layouts and a not-so-new Marvel newcomer John Buscema pencilling under Frank Giacoia inks. |

| Anyone care to take a guess as to who the villains might be in Strange Tales 150's SHIELD tale? |

What stands out most about this episode of SHIELD is just how good Buscema's drawing is compared to the revolving roster of artists that has lead up to this point. His skill with characterful faces and action figurework is superb, and it's a real shame that he didn't stay on SHIELD. But if he had, then we probably wouldn't have had the incredible work of the artist who would arrive with the following issue of Strange Tales.

In the meantime, John Buscema would go on to draw three fill-issues of the Hulk series in Tales to Astonish before getting the regular gig as pencil artist on The Avengers ... a series he would draw for the next 30 issues or so, as well as branching out as the main artist on The Sub-Mariner and The Silver Surfer during the same period.

Overall, this early run of SHIELD tales feels a little unsatisfactory, but I can't make up my mind whether this is because I now know how good the subsequent run - written and drawn by Jim Steranko - would be. On balance, that's probably not the case, because I wasn't mad about these comics at the time, either.

At some point in the future, I will take a look at Steranko's sublime run on SHIELD, a job that will not seem like a chore at all.

Next: Marvel Bullpen Bulletins

Nhận xét

Đăng nhận xét