THE SWINGING SIXTIES was a brilliant time to be growing up. Popular culture was suddenly being driven by young customers who wanted their music, fashion and movies to be different from their parents'. But it didn't happen overnight. It took a few years - from the 1962 release of The Beatles "Love Me Do" to around 1966 - to take hold properly.

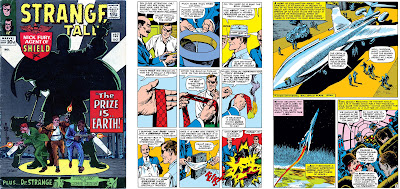

During those formative years, the things most important in my life were The (tv) Avengers (from series 4, 1965), The Man from UNCLE (1965) and Marvel Comics. So you can imagine how happy I was when Stan and Jack debuted Nick Fury, Agent of SHIELD - Supreme Headquarters International Espionage Law-enforcement Division - in Strange Tales 135 (Aug 1965) ... though that wasn't the first episode I saw. I came into the series with Strange Tales 139 (Dec 1965), and was at a bit of a loss to figure out what was going on. I recognised Tony Stark - who seemed to be SHIELD's chief technical officer - as Iron Man from sister publication Tales of Suspense.

I also recognised Dum-Dum Dugan and Gabe Jones from the Sgt Fury comics, though I was puzzled as to how they looked so young 20 years after WW2. Clearly I had to go back and fill in the gaps, by tracking down the earlier issues of Strange Tales.

A few months earlier, Stan had told the story of how Fury had met Reed Richards - then a major with the O.S.S (Office of Strategic Services) - during WW2 in the pages of Sgt Fury 3 (Aug 1963). The incident was more of a cameo for the future Mr Fantastic, though it is referenced in FF21.

By the time Fury shows up in Strange Tales 135's inaugural SHIELD tale, the CIA colonel has acquired his eyepatch, if not the security clearance to be forewarned of the SHIELD initiative.

That first SHIELD story is brimming with brilliant ideas. Though it does owe a debt to the James Bond movies Goldfinger (1964) and Thunderball (1965), and something more to the Man from UNCLE tv series, the mis-en-scene of Agent of SHIELD averages one fabulous concept per page across its 12-page running time.

The story begins with a befuddled Colonel Nick Fury undergoing a body scan in an undisclosed location. It's part of the process of creating LMDs (Life Model Decoys), lifelike androids designed to draw fire from an unknown but expected enemy. And draw fire they do ... as Fury is whisked away in a sporty Porsche, headed for the next phase of his induction. But Fury and the unnamed driver don't get far before the enemy renews its attack, dropping napalm from a fighter jet on top of the car. To Fury's astonishment, the car sails unharmed through the inferno then the driver takes out the jet with a pair of rear-mounted Sidewinder missiles and finally the Porsche converts to an air-car and flies upwards. The driver explains that these devices have been created by an international organisation called SHIELD and the assassins work for a group of criminal fanatics called Hydra.

We then switch scenes to Hydra's secret headquarters where the failed assassin is reporting to his boss, The Imperial Hydra. Understandably, the chief is not best pleased his people failed to kill Fury and orders the assassin to fight for his life, unarmed, on the Pendulums of Doom.

Meanwhile, Fury is welcomed to SHIELD HQ by industrialist and weapons manufacturer Tony Stark. Stark reveals that Fury is needed to head the fledgling SHIELD. Though Fury is doubtful, Stark points out that his lifetime of exemplary service qualifies him as the only man for the job. At that moment, Fury notices a wire protruding from the base of a chair and, ripping the seat from its moorings, heaves it out a handy window. Turning the page, we finally see SHIELD's headquarters - a battleship-sized airborne carrier, hovering a mile or so above the ground. It's one of Kirby's greatest moments and one of my all-time favourite "reveals" in a Silver-Age Marvel comic.

Instinctively, Fury takes charge, barking orders to have the heli-carrier secured so any would-be assassins can't escape. It's this that finally convinces Fury. "Someone has to smash Hydra," he observes. "It might as well be me."

For the most part, the first episode of the SHIELD series feels like a Kirby production. It's brimming with super-cool concepts, taking the best from Bond and UNCLE and giving the whole mix an injection of storytelling steroids. This was both a blessing and a curse. Everyone, including Stan, seems to be in an all-fire hurry to cash in on the spy craze without a clear direction on where to take Colonel Nick Fury next. As a result, the next instalment of SHIELD was a bit of a placeholder.

Strange Tales 136 (Sep 1965), "Find Fury or Die", had finished art by industry veteran John Severin over Jack Kirby layouts. Stan made a bit of a fuss about having Severin back, who'd been one of his mainstay artists at Atlas back in the 1950s.

Severin graduated high school in 1940 and managed for a while on his income from The Hobo News, but needed an actual income, so took a job making munitions for the British and French war effort. But after the US was drawn into the war, Severin joined up and served initially in the US Army, ending up in the Army Air Corps where he failed the test to be a pilot due to colour-blindness and found himself working in the camouflage unit.

When he got out of the army in 1946, Severin set his sights on a career as an artist. "I had decided to exhibit some paintings of mine in a High School of Music and Art exhibition for the alumni," he told Squa Tront magazine in 2005. "Charlie Stern was in charge of it, so I went to see him at his studio. He was the 'Charles' of the Charles William Harvey Studio, the other two being William Elder and Harvey Kurtzman. They asked me if I'd like to rent space with them there. I did, and started working with them. When Charlie left ... I became the third man, but they didn't want to change it to John William Harvey Studio, so they left the name ... Harvey was doing comics, Willie and Charlie were doing advertising stuff, and I just joined in ... design work, logos for toy boxes, logos for candy boxes, cards to be included in the candy boxes."

But it was actually at Crestwood Comics that Severin started drawing comics. Thinking that comics were easy money, he worked up some samples with Will Elder and went to see Joe Simon and Jack Kirby.

Yet the Grand Comicbook Database has Severin's first strip work as the six-page story "My Hobby ... Murder!" for Lawbreakers Always Lose 3 (Aug 1948), a Timely Comic. The next credit is the cover for Justice 5 (Sep 1948), also Timely. So WIKIpedia's claim that Severin's first published work was for Simon and Kirby at Crestwood looks to be in some doubt - though it's perfectly possible that the story in Headline Comics 32 (Oct-Nov 1948), "The Clue of the Horoscope", was drawn before the Timely jobs.

Severin would continue drawing for both Crestwood/Prize and for Timely/Atlas into the early 1950s, tackling every genre thrown at him - war, romance, western and crime. He drew his last Atlas story of this period for Black Rider 10 (Sep 1950), and a few months later drew his first breakthrough story for the legendary EC Comics for editor Harvey Kurtzman's Two-Fisted Tales 19 (Jan-Feb 1951) ... the terrific "War Story!"

Severin continued to draw - mostly war tales - for both EC and Prize right through to the summer of 1954 ... contributing his most memorable work for Frontline Combat, Mad and Two-Fisted Tales which he edited for the last six issues of its run (36 - 41). Then perhaps sensing which way the wind was blowing, started drawing for Atlas again not long before EC was going out of business. "Although I considered myself a freelancer, EC had come very close to being home to me," Severin told The Mirkwood Times in 1973. We all felt the loss of camaraderie which we'd had for one another. But most of all losing a bossman like Bill Gaines overnight was a fairly sorrowful event." By the time EC sputtered its last breath in mid-1955, Severin was drawing exclusively for Atlas.

For Stan Lee, Severin worked on staff in the Bullpen, drawing war and westerns, horror and humour in an unbroken stream from 1955 to 1957. "I ended up in this big bullpen sitting next to Bill Everett and Joe Maneely. And across was Carl Burgos, Sol Brodsky," Severin told The Comics Journal. "Joe Maneely and I used to swap artwork back and forth. He would draw a page with all this stuff and leave out the backgrounds ... And I would sit there and draw in the saloons and all this stuff in simple outlines. In the meantime, he's doing the same thing with one of my jobs. Sometimes we'd have the same story! He'd be doing one page and I'd be doing the other. He'd do the first; I'd do the second. He'd do the third, and so on and so forth." Then came the great Atlas Implosion and Severin was out of a steady job again. He must have thought he had the worst luck.

Fortunately, Severin still had his Prize work. In early 1958 he picked up some fill-in jobs for Charlton and DC, then landed his next major client in the Mad knock-off Cracked magazine, to which he would contribute regularly for the next 27 years.

Then, as 1959 hoved into view, Stan Lee was commissioning work once more for the fledgling "MC" comics he was editing under Martin Goodman. Severin was a natural for the surviving Kid Colt and he did a few jobs for the Marvel Westerns before concentrating his efforts on Cracked magazine into the early 1960s.

In the mid 1960s, Severin branched out again and started working for both Stan Lee on the SHIELD series in Strange Tales and for Jim Warren on the horror mags Creepy and Eerie, contributing some magnificent stories to Warren's Blazing Combat. Then in 1967, Severin settled in as the regular inker on Sgt Fury, working over Dick Ayers pencils, delivering the best-drawn run on the character. He would go on to ink a marvellous run of The Incredible Hulk (141-157) over Herb Trimpe's pencils and draw Kull the Conquerer with his sister Marie.

John Severin continued to draw for Marvel, Warren, Charlton and most importantly Cracked through the 1980s. "When I win the PowerBall I think I might [retire]," he told The Comics Journal in 1999, "but until then I'll just go right on. No, I enjoy doing things. I don't like to sit around doing nothing. Once in a while, I love to.

"I don't really have any real regrets or anything, but I don't know whether I've accomplished anything or not. Since I can't remember much of the time ..."

Severin received an Inkpot Award in 1998 and was inducted into the Will Eisner Award Hall of Fame in 2003.

John Severin died on 12 February 2012 at the age of 90. He was survived by his wife Michelina, his six children and his sister Marie.

Once in the barber shop, Fury alerts the SHIELD operatives that he's being followed, and an elaborate defence protocol is set in motion. Outside, the Hydra operatives are calling for backup, and a squadron of airborne Hydra goons is soon jetting towards the barber shop.

But while waiting for the Hydra goons to arrive, Fury and his team capture the trailing agents, hypnotise them, then turn them loose. The hypnotised Hydra men tell the flying goon squad that the real SHIELD HQ is down the road, inside a fake warehouse.

The Hydra goons then try to use a truck-mounted laser cannon to cut through the warehouse door, but are trapped inside a giant steel cell that erupts out of the ground.

The threat averted, Fury then reflects on how this war isn't going to be over any time soon.

As much fun as the episode is, it really doesn't amount to anything very much. All we're seeing here is Kirby - lacking direction from Stan Lee - filling the pages with ideas swiped from other spy shows and movies. There's no progression of the story. We don't find out anything new about the characters. Even the scene where the failed Hydra operative pays for his failure with his life is taken from the scene in Thunderball where Blofeld electrocutes a subordinate who fails to deliver - and we'd already had that schtick in the previous SHIELD episode.

Strange Tales 137 (Oct 1965) didn't do any more for progressing the plot than issue 136 did. There's some tradecraft in which some microfilm is passed from SHIELD agent to agent - on a train then on to a car which turns into a submarine - as Hydra goons close the net. The microfilm contained the location of the Hydra base which is due to launch an orbiting bomb, the Betatron, and thus hold mankind to ransom. Then Fury decides to take a hand and fly to the Balkans personally to find and destroy the bomb.

However, Strange Tales 138 (Nov 1965) picks up the pace a little and we see the bigger plan behind Hydra's seemingly pointless attacks on SHIELD. It's as if Stan had learned his lesson from those first few Captain America solo stories where he'd left Jack Kirby to his own devices a little too long. Fury arrives in the Balkans just a little too late to prevent Hydra launching the Betatron and now is left trying to figure out how to bring the orbiting bomb down without drenching the entire planet in deadly fallout. It turns out Tony Stark has an answer ... the Brainosaur. But before he can reveal its secret to Fury, Hydra goons invade the factory and capture Fury. The episode closes with the intrepid head of SHIELD dragged helpless before the Imperial Hydra.

My suspicion is that Stan had realised that simply having Hydra constantly attacking SHIELD, with SHIELD brushing it off like it's nothing, wasn't the way to generate a sense of danger and get the fans rooting for the good guys. Placing Fury in actual jeopardy feels more like Stan's idea and makes me think that this was the point where Stan started earning his co-plotter credit.

As I mentioned earlier, Strange Tales 139 (Nov 1965) had been my first experience of SHIELD. And all in all, it's a pretty good place to join the story, if a little confusing. With Fury locked up in a Hydra cell and fed dried rations that fizz like fireworks when exposed to the air, it seems there's no way out. Until Fury uses his exploding shirt (revealed in Strange Tales 137, thought I wouldn't have known that) to blast his way out of the cell, and is helped by the Imperial Hydra's beautiful assassin daughter. I was more able to forgive that cliche back in 1966 than I would be today. At the same time that Tony Stark is preparing the Braino-saur - a robot spacecraft that can disarm the Betatron in orbit - the ex-Howlers are invading Hydra's base in an attempt to free Fury. In the final panels, The Imperial Hydra wrestles with his conscience, hoping his own daughter won't be collateral damage in the ensuing battle.

With Kirby again on layouts, John Severin is gone and new addition to the Bullpen Joe Sinnott is providing finished pencils and inks. Sinnott had taken over inking Fantastic Four from Vince Colletta the same month, so Stan was looking to fill his spare moments with additional work, I'm thinking. Stranger was that John Severin didn't stick around, despite the build-up Stan had given him in Strange Tales 136. He wouldn't return to Marvel for two years, when he began inking Sgt Fury with issue 44.

Strange Tales 140 (Jan 1966) was more Tony Stark's heroic moment rather than Fury's. Piloting the Braino-saur, Stark disarms the Betatron Bomb in space, rendering it so much space junk. Fury, on the other hand, doesn't do a great deal other than keep the Imperial Hydra's daughter - Agent G - company while the Howlers and the Agents of SHIELD clean out Hydra HQ.

In the ensuing confusion, the Imperial Hydra escapes and it's revealed that he's not in reality the CEO and chief stockholder - Leslie Farrington - of Imperial Industries as we've been led to suspect, but actually Farrington's lowly assistant, Arnold Brown. The episode ends with Brown's finger poised over the destruct button of Hydra HQ, even though he knows his daughter is there with Fury.

Strange Tales 141 (Feb 1966) is a bit of a strange entry in the early SHIELD adventures. The first half mops up the last few details from the Imperial Hydra saga and the remaining five pages kick off a new adventure, "Operation: Brainblast", introducing SHIELD's ESP Division in the process.

This first SHIELD story arc is nothing special and, despite Jack Kirby back on full art chores on Strange Tales 141, it would only be for a couple of issues and then he'd be back on layouts for another new (to Marvel) artist.

Looking back now, this is probably why back during the 1960s I liked the SHIELD series well enough, but I never loved it. Overall it lacked a cohesiveness, and it desperately needed a firmer hand from Stan to bring it under control and give it some direction. Ironically, it wouldn't be Stan that would later take SHIELD from a "b" series to a world-beater, but that's a story for another time.

Meanwhile, the series would continue with a revolving door of pencil artists for the next few issues ... we'll cover those next time.

Next: More spy stuff and John Buscema's first work for Marvel Comics

During those formative years, the things most important in my life were The (tv) Avengers (from series 4, 1965), The Man from UNCLE (1965) and Marvel Comics. So you can imagine how happy I was when Stan and Jack debuted Nick Fury, Agent of SHIELD - Supreme Headquarters International Espionage Law-enforcement Division - in Strange Tales 135 (Aug 1965) ... though that wasn't the first episode I saw. I came into the series with Strange Tales 139 (Dec 1965), and was at a bit of a loss to figure out what was going on. I recognised Tony Stark - who seemed to be SHIELD's chief technical officer - as Iron Man from sister publication Tales of Suspense.

I also recognised Dum-Dum Dugan and Gabe Jones from the Sgt Fury comics, though I was puzzled as to how they looked so young 20 years after WW2. Clearly I had to go back and fill in the gaps, by tracking down the earlier issues of Strange Tales.

SURVIVING WW2

Of course, the SHIELD series wasn't the first time Nick Fury had appeared in a contemporary Marvel Comics setting. I was already aware of his guest-spot in Fantastic Four 21 (Dec 1963), which I'd seen the previous year. In that, Fury - by 1963 a colonel in the CIA - is the catalyst that brings the FF back together after the Hate Monger's ray makes them hate each other.A few months earlier, Stan had told the story of how Fury had met Reed Richards - then a major with the O.S.S (Office of Strategic Services) - during WW2 in the pages of Sgt Fury 3 (Aug 1963). The incident was more of a cameo for the future Mr Fantastic, though it is referenced in FF21.

By the time Fury shows up in Strange Tales 135's inaugural SHIELD tale, the CIA colonel has acquired his eyepatch, if not the security clearance to be forewarned of the SHIELD initiative.

That first SHIELD story is brimming with brilliant ideas. Though it does owe a debt to the James Bond movies Goldfinger (1964) and Thunderball (1965), and something more to the Man from UNCLE tv series, the mis-en-scene of Agent of SHIELD averages one fabulous concept per page across its 12-page running time.

The story begins with a befuddled Colonel Nick Fury undergoing a body scan in an undisclosed location. It's part of the process of creating LMDs (Life Model Decoys), lifelike androids designed to draw fire from an unknown but expected enemy. And draw fire they do ... as Fury is whisked away in a sporty Porsche, headed for the next phase of his induction. But Fury and the unnamed driver don't get far before the enemy renews its attack, dropping napalm from a fighter jet on top of the car. To Fury's astonishment, the car sails unharmed through the inferno then the driver takes out the jet with a pair of rear-mounted Sidewinder missiles and finally the Porsche converts to an air-car and flies upwards. The driver explains that these devices have been created by an international organisation called SHIELD and the assassins work for a group of criminal fanatics called Hydra.

We then switch scenes to Hydra's secret headquarters where the failed assassin is reporting to his boss, The Imperial Hydra. Understandably, the chief is not best pleased his people failed to kill Fury and orders the assassin to fight for his life, unarmed, on the Pendulums of Doom.

Meanwhile, Fury is welcomed to SHIELD HQ by industrialist and weapons manufacturer Tony Stark. Stark reveals that Fury is needed to head the fledgling SHIELD. Though Fury is doubtful, Stark points out that his lifetime of exemplary service qualifies him as the only man for the job. At that moment, Fury notices a wire protruding from the base of a chair and, ripping the seat from its moorings, heaves it out a handy window. Turning the page, we finally see SHIELD's headquarters - a battleship-sized airborne carrier, hovering a mile or so above the ground. It's one of Kirby's greatest moments and one of my all-time favourite "reveals" in a Silver-Age Marvel comic.

Instinctively, Fury takes charge, barking orders to have the heli-carrier secured so any would-be assassins can't escape. It's this that finally convinces Fury. "Someone has to smash Hydra," he observes. "It might as well be me."

For the most part, the first episode of the SHIELD series feels like a Kirby production. It's brimming with super-cool concepts, taking the best from Bond and UNCLE and giving the whole mix an injection of storytelling steroids. This was both a blessing and a curse. Everyone, including Stan, seems to be in an all-fire hurry to cash in on the spy craze without a clear direction on where to take Colonel Nick Fury next. As a result, the next instalment of SHIELD was a bit of a placeholder.

Strange Tales 136 (Sep 1965), "Find Fury or Die", had finished art by industry veteran John Severin over Jack Kirby layouts. Stan made a bit of a fuss about having Severin back, who'd been one of his mainstay artists at Atlas back in the 1950s.

WHO THE HECK IS JOHN SEVERIN?

John Powers Severin was born on 26 December 1921 in Jersey City, New Jersey. While at The High School of Music and Art in New York City, he contributed cartoons to The Hobo News (an early version of The Big Issue), receiving payment of one dollar per cartoon. As Severin explained in a 1999 Comics Journal interview: "I was sometimes selling 19 or 20 of them a week. Not every week, naturally. But I didn't have to get a regular job to carry me through high school. It was almost every week—not every week—but almost every week. I didn't have to get a job. I hated to work, I'll tell you. I didn't have to get a job then, because I was in high school." Severin's schoolmates were Harvey Kurtzman, Will Elder, Al Jaffee and Al Feldstein.Severin graduated high school in 1940 and managed for a while on his income from The Hobo News, but needed an actual income, so took a job making munitions for the British and French war effort. But after the US was drawn into the war, Severin joined up and served initially in the US Army, ending up in the Army Air Corps where he failed the test to be a pilot due to colour-blindness and found himself working in the camouflage unit.

When he got out of the army in 1946, Severin set his sights on a career as an artist. "I had decided to exhibit some paintings of mine in a High School of Music and Art exhibition for the alumni," he told Squa Tront magazine in 2005. "Charlie Stern was in charge of it, so I went to see him at his studio. He was the 'Charles' of the Charles William Harvey Studio, the other two being William Elder and Harvey Kurtzman. They asked me if I'd like to rent space with them there. I did, and started working with them. When Charlie left ... I became the third man, but they didn't want to change it to John William Harvey Studio, so they left the name ... Harvey was doing comics, Willie and Charlie were doing advertising stuff, and I just joined in ... design work, logos for toy boxes, logos for candy boxes, cards to be included in the candy boxes."

But it was actually at Crestwood Comics that Severin started drawing comics. Thinking that comics were easy money, he worked up some samples with Will Elder and went to see Joe Simon and Jack Kirby.

Yet the Grand Comicbook Database has Severin's first strip work as the six-page story "My Hobby ... Murder!" for Lawbreakers Always Lose 3 (Aug 1948), a Timely Comic. The next credit is the cover for Justice 5 (Sep 1948), also Timely. So WIKIpedia's claim that Severin's first published work was for Simon and Kirby at Crestwood looks to be in some doubt - though it's perfectly possible that the story in Headline Comics 32 (Oct-Nov 1948), "The Clue of the Horoscope", was drawn before the Timely jobs.

Severin would continue drawing for both Crestwood/Prize and for Timely/Atlas into the early 1950s, tackling every genre thrown at him - war, romance, western and crime. He drew his last Atlas story of this period for Black Rider 10 (Sep 1950), and a few months later drew his first breakthrough story for the legendary EC Comics for editor Harvey Kurtzman's Two-Fisted Tales 19 (Jan-Feb 1951) ... the terrific "War Story!"

Severin continued to draw - mostly war tales - for both EC and Prize right through to the summer of 1954 ... contributing his most memorable work for Frontline Combat, Mad and Two-Fisted Tales which he edited for the last six issues of its run (36 - 41). Then perhaps sensing which way the wind was blowing, started drawing for Atlas again not long before EC was going out of business. "Although I considered myself a freelancer, EC had come very close to being home to me," Severin told The Mirkwood Times in 1973. We all felt the loss of camaraderie which we'd had for one another. But most of all losing a bossman like Bill Gaines overnight was a fairly sorrowful event." By the time EC sputtered its last breath in mid-1955, Severin was drawing exclusively for Atlas.

For Stan Lee, Severin worked on staff in the Bullpen, drawing war and westerns, horror and humour in an unbroken stream from 1955 to 1957. "I ended up in this big bullpen sitting next to Bill Everett and Joe Maneely. And across was Carl Burgos, Sol Brodsky," Severin told The Comics Journal. "Joe Maneely and I used to swap artwork back and forth. He would draw a page with all this stuff and leave out the backgrounds ... And I would sit there and draw in the saloons and all this stuff in simple outlines. In the meantime, he's doing the same thing with one of my jobs. Sometimes we'd have the same story! He'd be doing one page and I'd be doing the other. He'd do the first; I'd do the second. He'd do the third, and so on and so forth." Then came the great Atlas Implosion and Severin was out of a steady job again. He must have thought he had the worst luck.

Fortunately, Severin still had his Prize work. In early 1958 he picked up some fill-in jobs for Charlton and DC, then landed his next major client in the Mad knock-off Cracked magazine, to which he would contribute regularly for the next 27 years.

Then, as 1959 hoved into view, Stan Lee was commissioning work once more for the fledgling "MC" comics he was editing under Martin Goodman. Severin was a natural for the surviving Kid Colt and he did a few jobs for the Marvel Westerns before concentrating his efforts on Cracked magazine into the early 1960s.

In the mid 1960s, Severin branched out again and started working for both Stan Lee on the SHIELD series in Strange Tales and for Jim Warren on the horror mags Creepy and Eerie, contributing some magnificent stories to Warren's Blazing Combat. Then in 1967, Severin settled in as the regular inker on Sgt Fury, working over Dick Ayers pencils, delivering the best-drawn run on the character. He would go on to ink a marvellous run of The Incredible Hulk (141-157) over Herb Trimpe's pencils and draw Kull the Conquerer with his sister Marie.

|

| Severin brought some class to the titles he worked on as inker for Marvel Comics during the 1970s, then at the age of 83, drew 2003's controversial re-imagining of Kid Colt Outlaw. |

"I don't really have any real regrets or anything, but I don't know whether I've accomplished anything or not. Since I can't remember much of the time ..."

Severin received an Inkpot Award in 1998 and was inducted into the Will Eisner Award Hall of Fame in 2003.

|

| John Severin: 26 December 1921 - 12 February 2012 |

DON'T YIELD, BACK SHIELD!

Like the first SHIELD episode, the second instalment was another Kirby catalogue of terrific ideas in search of a story. Dastardly agents of Hydra monitor Nick Fury's every move, dogging his steps all the way to his ground-based HQ, a barber shop (a nod to the tailor shop in Man from UNCLE).Once in the barber shop, Fury alerts the SHIELD operatives that he's being followed, and an elaborate defence protocol is set in motion. Outside, the Hydra operatives are calling for backup, and a squadron of airborne Hydra goons is soon jetting towards the barber shop.

But while waiting for the Hydra goons to arrive, Fury and his team capture the trailing agents, hypnotise them, then turn them loose. The hypnotised Hydra men tell the flying goon squad that the real SHIELD HQ is down the road, inside a fake warehouse.

|

| Leaving no stone unturned in his quest to swipe from every contemporary spy series he could, Jack Kirby manages to squeeze in James Bond's iconic jetpack from Thunderball. |

|

| And while we're at it, let's have the equally iconic laser gun from Goldfinger. We can use it to burn our way into the SHIELD warehouse, just like Goldfinger uses his to burn his way into Fort Knox. |

As much fun as the episode is, it really doesn't amount to anything very much. All we're seeing here is Kirby - lacking direction from Stan Lee - filling the pages with ideas swiped from other spy shows and movies. There's no progression of the story. We don't find out anything new about the characters. Even the scene where the failed Hydra operative pays for his failure with his life is taken from the scene in Thunderball where Blofeld electrocutes a subordinate who fails to deliver - and we'd already had that schtick in the previous SHIELD episode.

Strange Tales 137 (Oct 1965) didn't do any more for progressing the plot than issue 136 did. There's some tradecraft in which some microfilm is passed from SHIELD agent to agent - on a train then on to a car which turns into a submarine - as Hydra goons close the net. The microfilm contained the location of the Hydra base which is due to launch an orbiting bomb, the Betatron, and thus hold mankind to ransom. Then Fury decides to take a hand and fly to the Balkans personally to find and destroy the bomb.

However, Strange Tales 138 (Nov 1965) picks up the pace a little and we see the bigger plan behind Hydra's seemingly pointless attacks on SHIELD. It's as if Stan had learned his lesson from those first few Captain America solo stories where he'd left Jack Kirby to his own devices a little too long. Fury arrives in the Balkans just a little too late to prevent Hydra launching the Betatron and now is left trying to figure out how to bring the orbiting bomb down without drenching the entire planet in deadly fallout. It turns out Tony Stark has an answer ... the Brainosaur. But before he can reveal its secret to Fury, Hydra goons invade the factory and capture Fury. The episode closes with the intrepid head of SHIELD dragged helpless before the Imperial Hydra.

My suspicion is that Stan had realised that simply having Hydra constantly attacking SHIELD, with SHIELD brushing it off like it's nothing, wasn't the way to generate a sense of danger and get the fans rooting for the good guys. Placing Fury in actual jeopardy feels more like Stan's idea and makes me think that this was the point where Stan started earning his co-plotter credit.

As I mentioned earlier, Strange Tales 139 (Nov 1965) had been my first experience of SHIELD. And all in all, it's a pretty good place to join the story, if a little confusing. With Fury locked up in a Hydra cell and fed dried rations that fizz like fireworks when exposed to the air, it seems there's no way out. Until Fury uses his exploding shirt (revealed in Strange Tales 137, thought I wouldn't have known that) to blast his way out of the cell, and is helped by the Imperial Hydra's beautiful assassin daughter. I was more able to forgive that cliche back in 1966 than I would be today. At the same time that Tony Stark is preparing the Braino-saur - a robot spacecraft that can disarm the Betatron in orbit - the ex-Howlers are invading Hydra's base in an attempt to free Fury. In the final panels, The Imperial Hydra wrestles with his conscience, hoping his own daughter won't be collateral damage in the ensuing battle.

With Kirby again on layouts, John Severin is gone and new addition to the Bullpen Joe Sinnott is providing finished pencils and inks. Sinnott had taken over inking Fantastic Four from Vince Colletta the same month, so Stan was looking to fill his spare moments with additional work, I'm thinking. Stranger was that John Severin didn't stick around, despite the build-up Stan had given him in Strange Tales 136. He wouldn't return to Marvel for two years, when he began inking Sgt Fury with issue 44.

Strange Tales 140 (Jan 1966) was more Tony Stark's heroic moment rather than Fury's. Piloting the Braino-saur, Stark disarms the Betatron Bomb in space, rendering it so much space junk. Fury, on the other hand, doesn't do a great deal other than keep the Imperial Hydra's daughter - Agent G - company while the Howlers and the Agents of SHIELD clean out Hydra HQ.

In the ensuing confusion, the Imperial Hydra escapes and it's revealed that he's not in reality the CEO and chief stockholder - Leslie Farrington - of Imperial Industries as we've been led to suspect, but actually Farrington's lowly assistant, Arnold Brown. The episode ends with Brown's finger poised over the destruct button of Hydra HQ, even though he knows his daughter is there with Fury.

Strange Tales 141 (Feb 1966) is a bit of a strange entry in the early SHIELD adventures. The first half mops up the last few details from the Imperial Hydra saga and the remaining five pages kick off a new adventure, "Operation: Brainblast", introducing SHIELD's ESP Division in the process.

This first SHIELD story arc is nothing special and, despite Jack Kirby back on full art chores on Strange Tales 141, it would only be for a couple of issues and then he'd be back on layouts for another new (to Marvel) artist.

Looking back now, this is probably why back during the 1960s I liked the SHIELD series well enough, but I never loved it. Overall it lacked a cohesiveness, and it desperately needed a firmer hand from Stan to bring it under control and give it some direction. Ironically, it wouldn't be Stan that would later take SHIELD from a "b" series to a world-beater, but that's a story for another time.

Meanwhile, the series would continue with a revolving door of pencil artists for the next few issues ... we'll cover those next time.

Next: More spy stuff and John Buscema's first work for Marvel Comics

Nhận xét

Đăng nhận xét