WAY BACK IN THE EARLY 1960s, my first exposure to actors dressed up as comic characters was in the movie serials I saw at Saturday Morning Pictures. I've mentioned here already that for a 10-year-old comics fan in the Sixties, there wasn't a great deal of choice when it came to superhero movies or tv shows. But we were able to see b-movie actors playing a couple of our favourite comic characters in serials like Captain Marvel (1940) and Batman (1943), and fake comic characters like Copperhead in The Mysterious Dr Satan (1941) and Rocket Man in King of the Rocket Men (1949).

Movie serials were mostly made by the b-movie divisions of the smaller, cheaper film studios, like Universal, Columbia and Republic - even poverty row's Monogram managed to churn out a few cliffhanger serials - and routinely comprised of 12 or 15 chapters running about 20 minutes. The first five minutes would recap the previous episodes, the remaining running time would be taken up with breakneck chases and lengthy gun battles or fist-fights in which no one would lose their hats, and each episode would end with the hero in some kind of completely inescapable trap, which we all knew he would escape from in the very next episode.

The earliest example of a comic character in a serial that I could find was Universal's Tailspin Tommy (1934), based on Hal Forrest's newspaper strip of the same name. I wouldn't have been familiar with the character as a kid - partly because we didn't really get the classic America comic strips in British newspapers, but mostly because Tailspin Tommy, lasting from 1928 until 1942, was finished long before I was born.

Trading on the public fascination with flying in the wake of Charles Lindbergh's trans-Atlantic flight in 1927, the strip told of the ambitious kid from Littleville, Colorado who gets a chance to be involved in aviation when mail pilot Milt Howe crashlands near his home. Landing a job at Three Point Airlines, Tommy eventually becomes a pilot and with his friend Skeeter and girlfriend Betty-Lou gets involved in all kinds of adventures.

The serial pretty much followed the strip's storyline and did well enough to spawn a sequel the following year, Tailspin Tommy in the Great Air Mystery (1935). It's not something I would have been much interested in as a youngster, with its corny situations and its "Aw, shucks" characters and anyway, by the 1960s, air travel had become commonplace.

No doubt encouraged by the modest success of its two Tailspin Tommy serials, Universal then struck a deal to buy a parcel of newspaper strips from market leader King Features Syndicate, and set about making one of the most expensive and successful serials of all time, Flash Gordon (1936).

Though far better remembered today, the Flash Gordon comic strip was created to cash in on the success of the Buck Rogers newspaper strip. King Features first tried to buy the rights to John Carter of Mars from Edgar Rice Burroughs but, unable to reach an agreement, finally turned to staff artist Alex Raymond and asked him to create a space opera character. The resulting strip takes its inspiration from the Philip Wylie novel, When Worlds Collide, later a George Pal movie, appropriating the ideas of a planet on a collision course with Earth, and an athletic hero and his girlfriend, accompanied by an elderly scientist, travelling to the planet in a rocket. The strip debuted in January 1934, scripted by Don Moore, though only Raymond's signature appeared on the strip.

For the serial's hero, Universal initially considered Jon Hall (who would later star with Maria Montez in several "Arabian Nights" type fantasy movies) but then cast Olympic swimmer Buster Crabbe. Crabbe had appeared a couple of years earlier in one of the first Tarzan serials, so with his hair bleached blond, he made the perfect Flash.

Crabbe had gone along to the audition for the role, with no expectation of winning the part. Watching Hall and others try out for the role from the sidelines, Crabbe was noticed by the serial’s producer, Henry MacRae. After a brief conversation, and with no audition at all, MacRae surprised Crabbe by offering him the part. Under contract to Paramount at the time, and not happy about it, Crabbe said he wasn't really that interested. “I honestly thought Flash Gordon was too far-out, and that it would flop at the box office. God knows I’d been in enough turkeys during my four years as an actor; I didn’t need another one.” But MacRae persisted, and finally Crabbe told him that it was up to Paramount. “If they say you can borrow me, then I’d be willing to play the part.”

The other bit of inspired casting was Charles Middleton as Ming the Merciless. So successful was Middleton in the role that although his Ming dies at the end of Flash Gordon, he would return to play the character twice more in Flash Gordon's Trip to Mars (1938) and Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe (1940).

Yet for all his physical resemblance the the Emperor of the Universe, Middleton is a little wooden in the role and speaks his lines as though he doesn't really understand what's going on. There's a scene in Episode 4 where Dr Zarkov, who has been forced to work in Ming's laboratory to ensure the safety of Flash and Dale, says to Ming, "I've discovered a new ray, which can be of great help in furthering your plan."

"H'mm," responds Ming. "Tell me about it."

"The ray is a variation of the one you've been using, but being of a higher frequency, it's much more flexible. It is picked up from the negative side rather than the positive."

"I see," says Ming, though it's pretty apparent that he doesn't.

The rest of the cast was rounded out by Jean Rogers as Dale Arden, Priscilla Lawson as Princess Aura and Frank Shannon as Dr Zarkov.

Rogers, real name Eleanor Dorothy Lovegren, had gotten into the movie business almost by accident, after winning a beauty contest at the age of 17 and being offered a movie contract at Warner Brothers. A year later, she moved to Universal and appeared in several of their series, including Secret Agent X-9 (1937). In Flash Gordon, she wasn't given much to do apart from squeal in terror and faint rather a lot. She did make a fetching Dale, though, styled in a series of brief outfits and her naturally dark hair dyed blonde.

Priscilla Lawson (b. Priscilla Shortridge) had been a professional model before winning the Miss Miami Beach content in 1935 and being offered a contract at Universal. Most her roles were bit parts, playing "Hatcheck girl (uncredited)", "Maid (uncredited)" and "Native girl (uncredited)" in a string of b-movies. Her breakthrough role as Princes Aura didn't do much for her career, and after leaving acting five years later she signed with the armed forces in WWII. The rumour that she lost a leg in an accident on active service has been denied by co-star Jean Rogers. Lawson died in 1958, aged 44, due to complications with a duodenal ulcer.

Frank Shannon started off in silent pictures around 1913, in The Prisoner of Zenda, but quickly took to stage acting. He didn't return to movies until 1921, where he would play a long succession of cops and cowboys, until making a cult name for himself as Dr Alexis Zarkov in the first Flash Gordon serial. He would go on to play in all three Flash Gordon serials, along with Buster Crabbe and Charles Middleton. He also had a continuing role as Captain MacTavish in the Torchy Blaine movie series, as well as appearing in the Batman and The Phantom serials.

Other names that turn up are Carroll Borland (the sexy vampiress from Mark of the Vampire, 1935) as a hand-maiden in Ming's throne room, Ray Corrigan (who went on to star in Undersea Kingdom and was later the monster in It the Terror from Beyond Space) as the Orangopoid, Eddie Parker (who was a stunt player in nearly every serial ever made and doubled for Lon Chaney as The Wolf Man in Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man) and Glenn Strange, who plays the Robot, Gocko and one of Ming's soldiers, was later famous for taking over the role of Frankenstein's Monster in House of Frankenstein (1944), House of Dracula (1945) and Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948).

This serial's budget of $360,000 was three times more than was usually spent on a cliffhanger movie in the 1930s. Yet despite its comparatively large budget, the serial was shot in six weeks with the cast and crew working many fourteen hour days, with an average of 85 set-ups a day.

"They started shooting Flash Gordon in October of 1935," said Buster Crabbe in a later interview, "and to bring it in on the six-week schedule, we had to average 85 set-ups a day. That means moving and rearranging the heavy equipment we had, the arc lights and everything, 85 times a day. We had to be in makeup every morning at seven, and on the set at eight ready to go. They’d always knock off for lunch, and then we always worked after dinner. They’d give us a break of a half-hour or 45 minutes and then we’d go back on the set and work until ten-thirty every night. It wasn’t fun, it was a lot of work!"

The producers also saved money by re-using many sets from other Universal films, such as the laboratory and crypt set from Bride of Frankenstein (1935), the castle interiors from Dracula's Daughter (1936), the idol from The Mummy (1932) and the opera house interiors from The Phantom of the Opera (1925). In addition, the outer walls of Ming's castle were actually the cathedral walls from The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923).

There's a few things that don't make sense about the plot. Why does Ming need Dr Zarkov's scientific ability to conquer the Universe, when he must have had his own scientists to build the technologically superior laboratory.

Much of the equipment in Ming's lab is Kenneth Strickfadden's static electricity machinery re-used from Frankenstein (1931). The equipment had also been used in the earlier Mask of Fu Manchu (1932), which Flash Gordon resembles in many ways.

Also, with all the technology as the disposal of the Hawkmen, for example the radium-powered engines holding their entire city suspended miles above the ground, you'd think they would have a better way to get radium into the "radium furnaces" that human slaves shovelling the ore in.

The sound effect of the rocket ship's propulsion sounds just like a propeller aircraft of the period. Jets hadn't been invented in 1936, so the producers reasoned that no one in the audience would know what a rocket engine would sound like.

The plot is pretty convoluted, and characters seem to switch allegiances from one episode to the next. Trying to keep score requires a checklist. Here's what I managed to figure out on a recent viewing:

Though by today's standards the serials may seem especially creaky - their production values are terrible, the acting is uniformly bad (though I would allow an exception in Buster Crabbe's case) and the special effects are far from convincing - they can also be enormously entertaining. And Flash Gordon is no exception. It's probably the best known serial of all, probably the most successful, and certainly the most influential.

For example, George Lucas originally wanted to make his next film after American Graffiti (1975) a remake of the Flash Gordon serial. However, unable to secure the rights from King Features (they'd already been optioned by Dino DeLaurentiis, and we all know how that turned out), Lucas was forced (no pun intended) to come up with his own story - and we also know how that turned out.

In the event, the Dino de Laurentiis version of Flash Gordon (1980) probably ranks as one of the worst movies ever made. It's wrong-headed on every level and it's pretty clear that neither de Laurentiis, nor director Mike Hodges, had any idea what made George Lucas' version of the space opera work. You'd have thought that given the source material, the budget and (some of) the talent involved, the movie version of Flash Gordon should have been pretty entertaining ... but sadly not. And for the most part, I blame the screenwriter.

For some reason, Lorenzo Semple Jr had become the go-to guy for comic book screen adaptations after he created the format and approach for the excreable Batman tv show in late 1965. Until Batman, Semple had been a jobbing tv writer with few teleplays of note on his resume, contributing to Kraft Suspense Theatre ("Knight's Gambit", 1964), The Rogues ("Death of a Fleming", 1964) and Burke's Law (three episodes, 1964-5).

Around the same time, he'd been hired by producer William Dozier to write a pilot for a new tv show called Number One Son, which would have featured the adventures of Charlie Chan's eldest boy, as a detective in San Francisco. Then, according to an interview Semple gave, at the eleventh hour network ABC decided they didn't want to run a show that had an ethnic lead. Dozier was apologetic and told Semple, "I owe you one." Well, that "one" was as the developer of the Batman show.

Despite the horror of Semple's campy approach to the only superhero show on television, he was suddenly the writer you went to if you wanted to a comics adaptation. And even more incredibly, though projects like the 1976, Semple-scripted King Kong remake bombed at the box office, producers still lined up to have Semple knock off contemptuously jokey scripts for projects that deserved better. And just in case you think I made the "contemptuously" bit up in my head, here's Semple's own thoughts on the subject.

"I have moderately short shrift for serious comic book fans," Semple told Starlog magazine in 1983. "It depends on how serious they are. Collecting comics is one thing. Reading them on a serious level is quite another. Collecting comics isn't much different from collecting old orange crate labels, it's part of American pop culture.

"But to think that comics are a legitimate form of artistic expression is utter nonsense. Nobody involved in the field in the early days looked on it as such. Comics are like primitive art. They should be read for fun. To pretend they're anything else is a gross exploitation of people who don't know any better.

"Being a comic book fan is a harmless neurosis, but it is one. And for those who live comics books, and would coin the term 'panelology' to describe their study of the form, you need say very little more to me about their intellectual tastes."

Not only did the first Flash Gordon serial spawn two sequels and a terrible 1980s remake, but Universal also cast Crabbe as the star of their serial adaptation of Flash Gordon rival Buck Rogers, which one can only surmise was green-lit because of the success of the Flash Gordon films. Ironic, eh?

Also part of the King Features package bought by Universal were:

Next: More superheroes on-screen

Movie serials were mostly made by the b-movie divisions of the smaller, cheaper film studios, like Universal, Columbia and Republic - even poverty row's Monogram managed to churn out a few cliffhanger serials - and routinely comprised of 12 or 15 chapters running about 20 minutes. The first five minutes would recap the previous episodes, the remaining running time would be taken up with breakneck chases and lengthy gun battles or fist-fights in which no one would lose their hats, and each episode would end with the hero in some kind of completely inescapable trap, which we all knew he would escape from in the very next episode.

The earliest example of a comic character in a serial that I could find was Universal's Tailspin Tommy (1934), based on Hal Forrest's newspaper strip of the same name. I wouldn't have been familiar with the character as a kid - partly because we didn't really get the classic America comic strips in British newspapers, but mostly because Tailspin Tommy, lasting from 1928 until 1942, was finished long before I was born.

Trading on the public fascination with flying in the wake of Charles Lindbergh's trans-Atlantic flight in 1927, the strip told of the ambitious kid from Littleville, Colorado who gets a chance to be involved in aviation when mail pilot Milt Howe crashlands near his home. Landing a job at Three Point Airlines, Tommy eventually becomes a pilot and with his friend Skeeter and girlfriend Betty-Lou gets involved in all kinds of adventures.

The serial pretty much followed the strip's storyline and did well enough to spawn a sequel the following year, Tailspin Tommy in the Great Air Mystery (1935). It's not something I would have been much interested in as a youngster, with its corny situations and its "Aw, shucks" characters and anyway, by the 1960s, air travel had become commonplace.

No doubt encouraged by the modest success of its two Tailspin Tommy serials, Universal then struck a deal to buy a parcel of newspaper strips from market leader King Features Syndicate, and set about making one of the most expensive and successful serials of all time, Flash Gordon (1936).

Though far better remembered today, the Flash Gordon comic strip was created to cash in on the success of the Buck Rogers newspaper strip. King Features first tried to buy the rights to John Carter of Mars from Edgar Rice Burroughs but, unable to reach an agreement, finally turned to staff artist Alex Raymond and asked him to create a space opera character. The resulting strip takes its inspiration from the Philip Wylie novel, When Worlds Collide, later a George Pal movie, appropriating the ideas of a planet on a collision course with Earth, and an athletic hero and his girlfriend, accompanied by an elderly scientist, travelling to the planet in a rocket. The strip debuted in January 1934, scripted by Don Moore, though only Raymond's signature appeared on the strip.

For the serial's hero, Universal initially considered Jon Hall (who would later star with Maria Montez in several "Arabian Nights" type fantasy movies) but then cast Olympic swimmer Buster Crabbe. Crabbe had appeared a couple of years earlier in one of the first Tarzan serials, so with his hair bleached blond, he made the perfect Flash.

Crabbe had gone along to the audition for the role, with no expectation of winning the part. Watching Hall and others try out for the role from the sidelines, Crabbe was noticed by the serial’s producer, Henry MacRae. After a brief conversation, and with no audition at all, MacRae surprised Crabbe by offering him the part. Under contract to Paramount at the time, and not happy about it, Crabbe said he wasn't really that interested. “I honestly thought Flash Gordon was too far-out, and that it would flop at the box office. God knows I’d been in enough turkeys during my four years as an actor; I didn’t need another one.” But MacRae persisted, and finally Crabbe told him that it was up to Paramount. “If they say you can borrow me, then I’d be willing to play the part.”

The other bit of inspired casting was Charles Middleton as Ming the Merciless. So successful was Middleton in the role that although his Ming dies at the end of Flash Gordon, he would return to play the character twice more in Flash Gordon's Trip to Mars (1938) and Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe (1940).

Yet for all his physical resemblance the the Emperor of the Universe, Middleton is a little wooden in the role and speaks his lines as though he doesn't really understand what's going on. There's a scene in Episode 4 where Dr Zarkov, who has been forced to work in Ming's laboratory to ensure the safety of Flash and Dale, says to Ming, "I've discovered a new ray, which can be of great help in furthering your plan."

"H'mm," responds Ming. "Tell me about it."

"The ray is a variation of the one you've been using, but being of a higher frequency, it's much more flexible. It is picked up from the negative side rather than the positive."

"I see," says Ming, though it's pretty apparent that he doesn't.

The rest of the cast was rounded out by Jean Rogers as Dale Arden, Priscilla Lawson as Princess Aura and Frank Shannon as Dr Zarkov.

Rogers, real name Eleanor Dorothy Lovegren, had gotten into the movie business almost by accident, after winning a beauty contest at the age of 17 and being offered a movie contract at Warner Brothers. A year later, she moved to Universal and appeared in several of their series, including Secret Agent X-9 (1937). In Flash Gordon, she wasn't given much to do apart from squeal in terror and faint rather a lot. She did make a fetching Dale, though, styled in a series of brief outfits and her naturally dark hair dyed blonde.

Priscilla Lawson (b. Priscilla Shortridge) had been a professional model before winning the Miss Miami Beach content in 1935 and being offered a contract at Universal. Most her roles were bit parts, playing "Hatcheck girl (uncredited)", "Maid (uncredited)" and "Native girl (uncredited)" in a string of b-movies. Her breakthrough role as Princes Aura didn't do much for her career, and after leaving acting five years later she signed with the armed forces in WWII. The rumour that she lost a leg in an accident on active service has been denied by co-star Jean Rogers. Lawson died in 1958, aged 44, due to complications with a duodenal ulcer.

Frank Shannon started off in silent pictures around 1913, in The Prisoner of Zenda, but quickly took to stage acting. He didn't return to movies until 1921, where he would play a long succession of cops and cowboys, until making a cult name for himself as Dr Alexis Zarkov in the first Flash Gordon serial. He would go on to play in all three Flash Gordon serials, along with Buster Crabbe and Charles Middleton. He also had a continuing role as Captain MacTavish in the Torchy Blaine movie series, as well as appearing in the Batman and The Phantom serials.

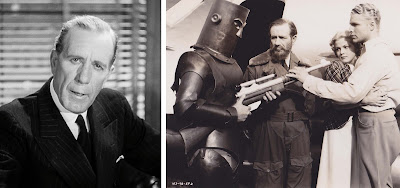

Other names that turn up are Carroll Borland (the sexy vampiress from Mark of the Vampire, 1935) as a hand-maiden in Ming's throne room, Ray Corrigan (who went on to star in Undersea Kingdom and was later the monster in It the Terror from Beyond Space) as the Orangopoid, Eddie Parker (who was a stunt player in nearly every serial ever made and doubled for Lon Chaney as The Wolf Man in Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man) and Glenn Strange, who plays the Robot, Gocko and one of Ming's soldiers, was later famous for taking over the role of Frankenstein's Monster in House of Frankenstein (1944), House of Dracula (1945) and Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948).

This serial's budget of $360,000 was three times more than was usually spent on a cliffhanger movie in the 1930s. Yet despite its comparatively large budget, the serial was shot in six weeks with the cast and crew working many fourteen hour days, with an average of 85 set-ups a day.

"They started shooting Flash Gordon in October of 1935," said Buster Crabbe in a later interview, "and to bring it in on the six-week schedule, we had to average 85 set-ups a day. That means moving and rearranging the heavy equipment we had, the arc lights and everything, 85 times a day. We had to be in makeup every morning at seven, and on the set at eight ready to go. They’d always knock off for lunch, and then we always worked after dinner. They’d give us a break of a half-hour or 45 minutes and then we’d go back on the set and work until ten-thirty every night. It wasn’t fun, it was a lot of work!"

The producers also saved money by re-using many sets from other Universal films, such as the laboratory and crypt set from Bride of Frankenstein (1935), the castle interiors from Dracula's Daughter (1936), the idol from The Mummy (1932) and the opera house interiors from The Phantom of the Opera (1925). In addition, the outer walls of Ming's castle were actually the cathedral walls from The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923).

There's a few things that don't make sense about the plot. Why does Ming need Dr Zarkov's scientific ability to conquer the Universe, when he must have had his own scientists to build the technologically superior laboratory.

|

| Ever cost-conscious, Universal would re-use much of the equipment Ken Strickfadden had made for Frankenstein (1931) and Mask of Fu Manchu (1932) for Ming's laboratory. |

Also, with all the technology as the disposal of the Hawkmen, for example the radium-powered engines holding their entire city suspended miles above the ground, you'd think they would have a better way to get radium into the "radium furnaces" that human slaves shovelling the ore in.

The sound effect of the rocket ship's propulsion sounds just like a propeller aircraft of the period. Jets hadn't been invented in 1936, so the producers reasoned that no one in the audience would know what a rocket engine would sound like.

The plot is pretty convoluted, and characters seem to switch allegiances from one episode to the next. Trying to keep score requires a checklist. Here's what I managed to figure out on a recent viewing:

- Prince Barin: rightful ruler of Mongo - enemy of Ming

- Prince Thun of the Lionmen - enemy of Ming

- King Kala of the Sharkmen - ally of Ming

- King Vultan of the Hawkmen - ally of Ming, but switches sides (distinguishable by his bellowing laughter just like the Brian Blessed's Vultan in the much later Dino de Laurentiis version, though both are following the characterisation from the original comic strip)

Though by today's standards the serials may seem especially creaky - their production values are terrible, the acting is uniformly bad (though I would allow an exception in Buster Crabbe's case) and the special effects are far from convincing - they can also be enormously entertaining. And Flash Gordon is no exception. It's probably the best known serial of all, probably the most successful, and certainly the most influential.

For example, George Lucas originally wanted to make his next film after American Graffiti (1975) a remake of the Flash Gordon serial. However, unable to secure the rights from King Features (they'd already been optioned by Dino DeLaurentiis, and we all know how that turned out), Lucas was forced (no pun intended) to come up with his own story - and we also know how that turned out.

In the event, the Dino de Laurentiis version of Flash Gordon (1980) probably ranks as one of the worst movies ever made. It's wrong-headed on every level and it's pretty clear that neither de Laurentiis, nor director Mike Hodges, had any idea what made George Lucas' version of the space opera work. You'd have thought that given the source material, the budget and (some of) the talent involved, the movie version of Flash Gordon should have been pretty entertaining ... but sadly not. And for the most part, I blame the screenwriter.

For some reason, Lorenzo Semple Jr had become the go-to guy for comic book screen adaptations after he created the format and approach for the excreable Batman tv show in late 1965. Until Batman, Semple had been a jobbing tv writer with few teleplays of note on his resume, contributing to Kraft Suspense Theatre ("Knight's Gambit", 1964), The Rogues ("Death of a Fleming", 1964) and Burke's Law (three episodes, 1964-5).

Around the same time, he'd been hired by producer William Dozier to write a pilot for a new tv show called Number One Son, which would have featured the adventures of Charlie Chan's eldest boy, as a detective in San Francisco. Then, according to an interview Semple gave, at the eleventh hour network ABC decided they didn't want to run a show that had an ethnic lead. Dozier was apologetic and told Semple, "I owe you one." Well, that "one" was as the developer of the Batman show.

|

| Lorenzo Semple Jr might have made a hash of the approach to the Flash Gordon screenplay, but at least we have Ornella Muti as Princess Aura. |

"I have moderately short shrift for serious comic book fans," Semple told Starlog magazine in 1983. "It depends on how serious they are. Collecting comics is one thing. Reading them on a serious level is quite another. Collecting comics isn't much different from collecting old orange crate labels, it's part of American pop culture.

"But to think that comics are a legitimate form of artistic expression is utter nonsense. Nobody involved in the field in the early days looked on it as such. Comics are like primitive art. They should be read for fun. To pretend they're anything else is a gross exploitation of people who don't know any better.

"Being a comic book fan is a harmless neurosis, but it is one. And for those who live comics books, and would coin the term 'panelology' to describe their study of the form, you need say very little more to me about their intellectual tastes."

|

| Killer Kane's thugs get the drop on Wilma Deering (Constance Moore) as Buck (Buster Crabbe) and Buddy (Jackie Moran) look helplessly on, in this scene from Chapter 1 of Buck Rogers (1939). |

Also part of the King Features package bought by Universal were:

- Ace Drummond (1936, based on another aviation strip, this time by WWI flyer Eddie Rickenbacker)

- Jungle Jim (1937, based on the Alex Raymond comic strip)

- Radio Patrol (1937, based on the police strip by Eddie Sullivan and Charles Schmidt)

- Secret Agent X-9 (1937, based on the strip by Dashiel Hammett and Alex Raymond)

- Tim Tyler's Luck (1937, based on the global adventure strip by Lyman Young)

- Red Barry (1938, based on the detective strip by Will Gould)

- Don Winslow (1942, based on the naval intelligence strip by Frank Martinek, spawning a sequel Don Winslow of the Coast Guard, 1943)

- Adventures of Smiling Jack (1943, based on the aviation strip by Zack Mosley)

- Dick Tracy (1937, based on the hugely successful police strip by Chester Gould)

- King of the Royal Mounted (1940, based on the strip by Stephen Slesinger. The sequel, King of the Mounties, 1942, appears to be uncredited and unauthorised)

- Adventures of Red Ryder (1940, based on the Western strip drawn by Fred Harman)

- Mandrake the Magician (1939, based on the long-running mystery strip by Lee Falk)

- Terry and the Pirates (1940, based on the legendary adventure strip by Milton Caniff)

- The Phantom (1943, based on the jungle superhero strip by Lee Falk)

- Brenda Starr (1945, based on the newspaper reporter strip by Dale Messick)

- Bruce Gentry - Daredevil of the Skies (1949, based on the aviation strip by Ray Bailey)

Next: More superheroes on-screen

Nhận xét

Đăng nhận xét