MARVEL COMICS WAS NEVER Martin Goodman's primary publishing interest. He had started up in the 1930s as a magazine publisher after first working as a circulation manager at Eastern Distributing Corporation, under future Archie Comics founder Louis Silberkleit.

When Eastern went out of business in 1932, Goodman joined several other investors, including Silberkleit, and founded Mutual Magazine Distributors as part owner, and was appointed editor of Mutual's sister company, Newsstand Publications Inc. Goodman's first publication for Newsstand was Western Supernovel Magazine, cover dated May 1933. The second issue was re-titled Complete Western Book Magazine, dated just two months later. The new publishing company quickly added further pulp magazines to its lineup, including All Star Adventure Fiction, Mystery Tales, Real Sports, Star Detective, the science fiction magazine Marvel Science Stories and the jungle-adventure Tarzan knock-off Ka-Zar.

In 1934, Mutual filed for bankruptcy, leaving Newsstand Publications in the lurch, Newsstand was unable to pay its printers and the company's assets were seized. Silberkleit decided it was prudent to abandon ship, but Goodman convinced the printers they'd have a better chance of getting their money if they allowed Newsstand to continue trading. Now as the sole owner, Goodman pulled the company back into profitability, and within a couple of years had moved to better offices in uptown Manhattan. "If you get a title that catches on," he told the trade magazine Literary Digest, "add a few more, and you're in for a nice profit." With Goodman, it was all about providing disposable entertainment as cheaply (to him) as possible. "Fans aren't interested in quality," he concluded.

Goodman's company didn't really have an identity. He'd publish each title under a different company name - Margood Publishing Corp, Marjean Magazine Corp and so on. That way, he could make sure that if one title ran into trouble, its misfortunes couldn't affect the rest of his publishing line. It was a practice he'd continue well into the 1960s.

As the 1930s wore on, sales of the fiction pulps were declining and there was a new fad gaining traction with kids at the newsstands ... comic books. National were having a great success with their costumed characters Superman and Batman, and Goodman, ever willing to jump on a bandwagon, contacted comic strip packager Funnies Inc and had them put together material for a 64 page book, Marvel Comics. The comic's first printing, cover dated Oct 1939 sold out its 80,000 print run in a week. Goodman immediately reprinted Marvel Comics 1 with "Nov" overprinted on the cover and this time sold out the 800,000 print run almost as quickly.

With a major hit on his hands, Goodman then quickly lured Funnies Inc editor Joe Simon away and set up what would come to be called Timely Comics. Daring Mystery Comics 1 (Jan 1940) quickly followed, then the Jack Kirby-drawn one-shot Red Raven Comics 1 (Aug 1940), which flopped and was quickly re-tooled as Human Torch 2 (Fall 1940).

Yet for all the initial success Goodman was having with his comic books, the pulp sales were in freefall, and Goodman began to transform the magazine part of his business into a low-end, traditional magazine publisher, putting out puzzle books, sports and movie fan mags, cartoon digests and "men's interest" magazines.

Through the 1940s, Goodman lavished far more attention on his magazines, or "slicks" as they were referred to, which he saw as far more reputable than the comics. Yet most of those publications are now lost in the mists of history. It's been very difficult to uncover any information on these magazines, beyond their subject matter.

One of his early magazines was a Readers' Digest knock-off called Popular Digest, the first issue of which was dated Sept 1939 and carried a strap-line of "Timely Topics Condensed" and was published by one of Goodman's shell-companies, Timely Publications, though the cover identifier Goodman was using around this time was Red Circle Magazines

But Goodman's most successful magazines - Stag and Male - were, ironically, a good deal less respectable than his comics line.

had begun in 1942 in response to the far more successful (and still extant) Esquire magazine. Goodman was always one to follow trends rather than to create them (as documented in umpteen other posts on this blog) and launched his version Stag in direct response. Or rather almost. The first issue of Stag was more of a compilation of cartoons from other magazines, printed on bulky pulp-style paper. But the following month, Goodman transformed the magazine and tried to publish something closer to the formula of Esquire.

Putting the two magazines side-by-side seems pretty damning. Though Stag was printed on much cheaper paper than Esquire, and used much lower profile contributors, there can be little doubt that Goodman was trying to cash in on the same market ... if I were less charitable, I might say he was trying to pass-off Stag as an Esquire stablemate.

But this new version of Stag didn't last either. After an internal scandal at Martin Goodman's company, where editor J. Alvin Kugelmass had been endorsing freelancers cheques to himself and cashing them, Stag shut down for a couple of months and returned as The Male Home Companion, for a single issue in October 1942.

A few years later, with sales on Goodman's comic line declining, Writers' Digest for August 1948 carried an announcement that Goodman was about to re-launch Stag magazine, with Stan Lee as editor. However, the plans fell through due to "distributor trouble" and the following year, another re-launch was announced, this time with Bruce Jacobs as editor.

Stag's subsequent success would launch a whole raft of what would come to be referred to affectionately as "men's sweat" magazines - a kind of cross between spicy pulps and coy girlie magazines. Completely by accident, Goodman had actually started a trend, and Stag and its other companion magazines would enjoy considerable success until the late 1960s, when market forces would compel Goodman to transform his line of men's mags into soft porn publications.

But in its heyday, Stag, along with stablemates Male and For Men Only, enjoyed the contributions of writers like Bruce Jay Friedman, Mario Puzo and Mickey Spillane, and artists like Norman Saunders, Earl Norem and Mort Kunstler.

As an impressionable lad of 11 or 12, I recall seeing issues of Stag and Male at the newsstands I would haunt while looking for Marvel Comics around 1963 and 1964. Despite the siren-call of the lurid cover art, I'd never pluck up the courage to pick one up and look inside, fearful that the proprietor would shoo me away if I were to show too much interest in these forbidden publications. So the contents will forever remain a mystery.

But for all that, it's as well to remember that Marvel's late Sixties and early Seventies foray into comic magazines was likely inspired by these slightly eccentric magazines.

But we readers didn't know any of that stuff. Oh, sure we knew something was happening with Marvel, but back then, I was just excited about additional, new Marvel Comics ... it didn't even occur to me that Marvel seemed to be doing better. Though the transition wasn't that smooth, because the same month that Hulk and Captain America took over Astonish and Suspense respectively, Stan had an 11-page Iron Man and an 11-page Sub-Mariner tale parked in the slightly odd Iron Man and Sub-Mariner.

I've always wondered why it was done that way. Did the Suits decide that launching the two brand-new titles, Iron Man and Sub-Mariner couldn't be done at the same time as Hulk and Captain America? That wouldn't make any sense, as in effect Hulk and Cap were just continuations of Astonish and Suspense, not additional titles. Or did Stan just miscalculate, and get his story-lengths in a muddle? I guess we'll never know ...

The first inkling I had about Marvel's aggressive expansion plans was when I stumbled across copies of Iron Man and Sub-Mariner 1 and Iron Man 1 in a small newsagent in Wemyss Bay in Scotland, in the summer of 1968. While I wasn't that mad about IM&SM1, I though the first issue of Iron Man was a very wonderful development, as I was a massive fan of Gene Colan at the time (still am) and the thought of 20 pages of Colan Iron Man at a time was beyond fantastic.

And as the Marvel explansion unfolded, there were more and more wonderful comics coming out. Jim Steranko's SHIELD comics deserve an entire blog post to themselves. Sub-Mariner and The Incredible Hulk in their own comics was okay. I hadn't been a great fan of Namor, though the John Buscema artwork was sublime. Kirby's Captain America title was great, of course, but then Cap was always my favourite Marvel character. And the Dr Strange book was also terrific. But in the house ads in those books we saw that there was even better things to come from Marvel, notably the Silver Surfer book (which also deserves its own posting). But the really intriguing thing was that second Spidey book, The Spectacular Spider-Man.

It wasn't all that obvious from the house ads just what we could expect. I wouldn't have noticed the 35c cover price in the ads, and it wouldn't have meant much to me if I had. And though I didn't track down a copy of the comic until a couple of years later, when I did finally find one I was pretty blown away. Where American comic readers might have been a bit disappointed that it was in black and white, that didn't bother me one bit. The skilful grey wash-tones more than made up for it. And that cover ... wow - a painting! I thought it was just incredible.

A couple of years earlier, someone had given my younger brother an illustrated Walt Disney storybook, but the pictures were full colour paintings of Mickey and Donald on a caravan holiday. I used to love those illustrations. Perhaps they were even by Carl Barks, but it's such a long time ago I can't be sure. The Spectacular Spider-Man cover was even better, because that was an oil painting of a super-hero - something fans may take for granted today, but back in 1968, it was nothing short of revolutionary.

Though it was based on a John Romita drawing, the execution of the cover painting was by Harry Rosenbaum. Little is known about Rosenbaum beyond his work for some of Goodman's men's magazines, and his later cover paintings for a couple of the Skywald mags put out by Sol Brodsky during his temporary split from Marvel Comics in the early 1970s.

The inside of the book was also pretty impressive. The story was mammoth length, at 52 pages, allowing for some spectacular six-page fight sequences by John Romita, and some great character scenes by Stan, featuring the usual supporting cast of Spider-Man. Further, Stan appears to have consciously pitched the story at an older readership, by not using a costumed villain, but rather a corrupt politician who uses a strength-enhanced monster to create chaos for his own nefarious purposes.

The reality was that independent publisher Jim Warren had been in this space for a couple of years already, aiming his own black and white mags, Creepy and Eerie, firmly at an older readership, with a horror anthology format that wasn't a million miles away from the classic EC Comics of the 1950s. But all that was lost on me, as I wouldn't come across these Warren comics until much later in my teens.

But for Stan, the experiment couldn't have been successful, because when the second issue of Spectacular Spider-Man (Nov 1968) came along, it was with four-colour interiors and a familiar costumed super-villain, The Green Goblin.

With the expanded space, Stan had encouraged John Romita to make the artwork, well, spectacular. So there were fewer panels on a page, with more full-page splashes dotted throughout the story. The supporting characters were once again in evidence, but I couldn't help feeling that this wasn't the direction Stan had envisaged for his magazine-size Spider-Man comic.

It was hard to see a difference between this story and what was going on in the regular Amazing Spider-Man title. If anything, the tale told in Spectacular Spider-Man 2 seemed to be simply marking time, as we end the story in exactly the same situation that we began it - with Norman Osborne back to his amnesiac state, oblivious that he'd ever been The Goblin and that Peter Parker was really Spider-Man. And there less of a feel that Stan was pitching this at an older audience than the regular comics.

I have no idea whether this was Stan's idea or if Goodman had imposed this package and approach on Stan in an effort to get better sales, but I think it was the wrong strategy and led to the magazine's cancellation.

It's doubtful that the trial was a success, as only the one issue ever appeared, though the character would continue in Goodman's men's sweat mags until the early 1970s, so it's not like there wasn't the material available.

By 1971, Goodman was halfway out the door at Marvel, and with the success of Robert E. Howard's Conan character in the Marvel colour books and Stan's ascendency to Publisher, Marvel took another swing at the black-and-white mag market with the introduction of the slightly racy Savage Tales, cover dated May 1971.

Besides the cover-featured Conan the Barbarian, the mag also gave us an equally titillating Ka-Zar story by John Buscema, a post apocalypse macho fantasy Femizons drawn by John Romita, a "blaxploitation" story, Black Brother by Denny O'Neil and Gene Colan and the first appearance of Man Thing by Gerry Conway and Gray Morrow (coincidently on sale the same month as DC's House of Secrets 92, which debuted the character Swamp Thing, creation of Gerry Conway's then-roommate Len Wein). But still Marvel struggled with the format.

The second issue of Savage Tales (Oct 1973) wouldn't come along for another two-and-a-half years, featuring mainly Barry Smith's Conan and a few reprints. And by this time, Marvel had already launched Dracula Lives (Apr 1973), Monsters Unleashed (Jun 1973), Vampire Tales (Jul 1973) and Tales of the Zombie (Aug 1973) in an all-out assault on beachhead Warren ...

Next: The Best Marvel Annual

When Eastern went out of business in 1932, Goodman joined several other investors, including Silberkleit, and founded Mutual Magazine Distributors as part owner, and was appointed editor of Mutual's sister company, Newsstand Publications Inc. Goodman's first publication for Newsstand was Western Supernovel Magazine, cover dated May 1933. The second issue was re-titled Complete Western Book Magazine, dated just two months later. The new publishing company quickly added further pulp magazines to its lineup, including All Star Adventure Fiction, Mystery Tales, Real Sports, Star Detective, the science fiction magazine Marvel Science Stories and the jungle-adventure Tarzan knock-off Ka-Zar.

|

| Martin Goodman quickly established his publishing philosophy - look at the newsstands, see what other houses were publishing then launch a copy. Rinse, repeat. |

Goodman's company didn't really have an identity. He'd publish each title under a different company name - Margood Publishing Corp, Marjean Magazine Corp and so on. That way, he could make sure that if one title ran into trouble, its misfortunes couldn't affect the rest of his publishing line. It was a practice he'd continue well into the 1960s.

As the 1930s wore on, sales of the fiction pulps were declining and there was a new fad gaining traction with kids at the newsstands ... comic books. National were having a great success with their costumed characters Superman and Batman, and Goodman, ever willing to jump on a bandwagon, contacted comic strip packager Funnies Inc and had them put together material for a 64 page book, Marvel Comics. The comic's first printing, cover dated Oct 1939 sold out its 80,000 print run in a week. Goodman immediately reprinted Marvel Comics 1 with "Nov" overprinted on the cover and this time sold out the 800,000 print run almost as quickly.

With a major hit on his hands, Goodman then quickly lured Funnies Inc editor Joe Simon away and set up what would come to be called Timely Comics. Daring Mystery Comics 1 (Jan 1940) quickly followed, then the Jack Kirby-drawn one-shot Red Raven Comics 1 (Aug 1940), which flopped and was quickly re-tooled as Human Torch 2 (Fall 1940).

Yet for all the initial success Goodman was having with his comic books, the pulp sales were in freefall, and Goodman began to transform the magazine part of his business into a low-end, traditional magazine publisher, putting out puzzle books, sports and movie fan mags, cartoon digests and "men's interest" magazines.

Through the 1940s, Goodman lavished far more attention on his magazines, or "slicks" as they were referred to, which he saw as far more reputable than the comics. Yet most of those publications are now lost in the mists of history. It's been very difficult to uncover any information on these magazines, beyond their subject matter.

|

| The first issue of Popular Digest was cover-dated September 1939, just one month ahead of Marvel Comics, and was published by Timely Publications. Coincidence? I think not. |

But Goodman's most successful magazines - Stag and Male - were, ironically, a good deal less respectable than his comics line.

had begun in 1942 in response to the far more successful (and still extant) Esquire magazine. Goodman was always one to follow trends rather than to create them (as documented in umpteen other posts on this blog) and launched his version Stag in direct response. Or rather almost. The first issue of Stag was more of a compilation of cartoons from other magazines, printed on bulky pulp-style paper. But the following month, Goodman transformed the magazine and tried to publish something closer to the formula of Esquire.

|

| An editor called J. Alvin Kugelmass brought the idea of imitating Esquire magazine on a much lower budget to Goodman, and the publisher - ever vigilant for a bargain - jumped in with both feet. |

But this new version of Stag didn't last either. After an internal scandal at Martin Goodman's company, where editor J. Alvin Kugelmass had been endorsing freelancers cheques to himself and cashing them, Stag shut down for a couple of months and returned as The Male Home Companion, for a single issue in October 1942.

A few years later, with sales on Goodman's comic line declining, Writers' Digest for August 1948 carried an announcement that Goodman was about to re-launch Stag magazine, with Stan Lee as editor. However, the plans fell through due to "distributor trouble" and the following year, another re-launch was announced, this time with Bruce Jacobs as editor.

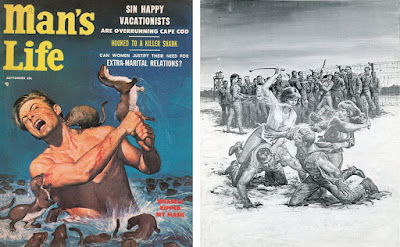

Stag's subsequent success would launch a whole raft of what would come to be referred to affectionately as "men's sweat" magazines - a kind of cross between spicy pulps and coy girlie magazines. Completely by accident, Goodman had actually started a trend, and Stag and its other companion magazines would enjoy considerable success until the late 1960s, when market forces would compel Goodman to transform his line of men's mags into soft porn publications.

But in its heyday, Stag, along with stablemates Male and For Men Only, enjoyed the contributions of writers like Bruce Jay Friedman, Mario Puzo and Mickey Spillane, and artists like Norman Saunders, Earl Norem and Mort Kunstler.

As an impressionable lad of 11 or 12, I recall seeing issues of Stag and Male at the newsstands I would haunt while looking for Marvel Comics around 1963 and 1964. Despite the siren-call of the lurid cover art, I'd never pluck up the courage to pick one up and look inside, fearful that the proprietor would shoo me away if I were to show too much interest in these forbidden publications. So the contents will forever remain a mystery.

But for all that, it's as well to remember that Marvel's late Sixties and early Seventies foray into comic magazines was likely inspired by these slightly eccentric magazines.

IT'S SPECTACULAR, ALL RIGHT ...

Back in 1957, when Goodman had found himself without a distributor, he was forced to go cap-in-hand to DC Publisher Jack Liebowitz and submit to a draconian eight-titles-a-month deal in order to get his comics on the stands. Though Liebowitz's Independent News allowed Goodman to add a few extra titles across the ten-year contract, Marvel was still only publishing 14 titles a month at the end of 1967. By the beginning of 1968, after Kinney National Company bought out DC Comics and Independent News, Marvel was finally freed up to expand its line of comics, and Goodman set about expanding his anthology titles Strange Tales, Tales of Suspense and Tales to Astonish into six titles. A year later, Independent News went out of business and both Marvel and Saturday Evening Post owner Curtis were sold to Perfect Film and Chemical Company, so it made sense for Curtis to distribute Marvel's comics.But we readers didn't know any of that stuff. Oh, sure we knew something was happening with Marvel, but back then, I was just excited about additional, new Marvel Comics ... it didn't even occur to me that Marvel seemed to be doing better. Though the transition wasn't that smooth, because the same month that Hulk and Captain America took over Astonish and Suspense respectively, Stan had an 11-page Iron Man and an 11-page Sub-Mariner tale parked in the slightly odd Iron Man and Sub-Mariner.

I've always wondered why it was done that way. Did the Suits decide that launching the two brand-new titles, Iron Man and Sub-Mariner couldn't be done at the same time as Hulk and Captain America? That wouldn't make any sense, as in effect Hulk and Cap were just continuations of Astonish and Suspense, not additional titles. Or did Stan just miscalculate, and get his story-lengths in a muddle? I guess we'll never know ...

The first inkling I had about Marvel's aggressive expansion plans was when I stumbled across copies of Iron Man and Sub-Mariner 1 and Iron Man 1 in a small newsagent in Wemyss Bay in Scotland, in the summer of 1968. While I wasn't that mad about IM&SM1, I though the first issue of Iron Man was a very wonderful development, as I was a massive fan of Gene Colan at the time (still am) and the thought of 20 pages of Colan Iron Man at a time was beyond fantastic.

|

| Incredibly, that tiny newsagent is still there in Wemyss Bay. I haven't been there for fifty years, but I'm very happy that one of my essential childhood haunts is still alive and well. |

It wasn't all that obvious from the house ads just what we could expect. I wouldn't have noticed the 35c cover price in the ads, and it wouldn't have meant much to me if I had. And though I didn't track down a copy of the comic until a couple of years later, when I did finally find one I was pretty blown away. Where American comic readers might have been a bit disappointed that it was in black and white, that didn't bother me one bit. The skilful grey wash-tones more than made up for it. And that cover ... wow - a painting! I thought it was just incredible.

A couple of years earlier, someone had given my younger brother an illustrated Walt Disney storybook, but the pictures were full colour paintings of Mickey and Donald on a caravan holiday. I used to love those illustrations. Perhaps they were even by Carl Barks, but it's such a long time ago I can't be sure. The Spectacular Spider-Man cover was even better, because that was an oil painting of a super-hero - something fans may take for granted today, but back in 1968, it was nothing short of revolutionary.

Though it was based on a John Romita drawing, the execution of the cover painting was by Harry Rosenbaum. Little is known about Rosenbaum beyond his work for some of Goodman's men's magazines, and his later cover paintings for a couple of the Skywald mags put out by Sol Brodsky during his temporary split from Marvel Comics in the early 1970s.

The inside of the book was also pretty impressive. The story was mammoth length, at 52 pages, allowing for some spectacular six-page fight sequences by John Romita, and some great character scenes by Stan, featuring the usual supporting cast of Spider-Man. Further, Stan appears to have consciously pitched the story at an older readership, by not using a costumed villain, but rather a corrupt politician who uses a strength-enhanced monster to create chaos for his own nefarious purposes.

The reality was that independent publisher Jim Warren had been in this space for a couple of years already, aiming his own black and white mags, Creepy and Eerie, firmly at an older readership, with a horror anthology format that wasn't a million miles away from the classic EC Comics of the 1950s. But all that was lost on me, as I wouldn't come across these Warren comics until much later in my teens.

But for Stan, the experiment couldn't have been successful, because when the second issue of Spectacular Spider-Man (Nov 1968) came along, it was with four-colour interiors and a familiar costumed super-villain, The Green Goblin.

With the expanded space, Stan had encouraged John Romita to make the artwork, well, spectacular. So there were fewer panels on a page, with more full-page splashes dotted throughout the story. The supporting characters were once again in evidence, but I couldn't help feeling that this wasn't the direction Stan had envisaged for his magazine-size Spider-Man comic.

It was hard to see a difference between this story and what was going on in the regular Amazing Spider-Man title. If anything, the tale told in Spectacular Spider-Man 2 seemed to be simply marking time, as we end the story in exactly the same situation that we began it - with Norman Osborne back to his amnesiac state, oblivious that he'd ever been The Goblin and that Peter Parker was really Spider-Man. And there less of a feel that Stan was pitching this at an older audience than the regular comics.

I have no idea whether this was Stan's idea or if Goodman had imposed this package and approach on Stan in an effort to get better sales, but I think it was the wrong strategy and led to the magazine's cancellation.

PUSSYCAT - A MARVEL ANOMALY

Right around the same time that Marvel were trying out the magazine format, Martin Goodman felt the time was right to experiment with a completely different kind of comic magazine. The Adventures of Pussycat had been running in five-page comic strip instalments in some of his men's magazines, like Stag, Men and Male, and had been written by Stan Lee, Ernie Hart and Larry Lieber and drawn by Wally Wood, Jim Mooney and the legendary Bill Ward. The strip was a low-budget riposte to Playboy's successful 1962-1988 "Little Annie Fanny", by Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder. Goodman had his magazine staff pull together nine episodes and shove them into a 64-page mag, the identical format to the first Spectacular Spider-Man magazine.It's doubtful that the trial was a success, as only the one issue ever appeared, though the character would continue in Goodman's men's sweat mags until the early 1970s, so it's not like there wasn't the material available.

MARVEL MAGS OF THE 1970s

The commercial failure of these three magazines at the end of the 1960s made Stan and Marvel shy of trying to compete with Warren's comics for quite some time. Right around the time that this was happening, Goodman was in the process of selling Marvel Comics to Perfect Film and Chemical Company, so it's quite possible that he hadn't considered a line of Marvel Comics magazines as a sustainable venture. He may well have just been piling on some product to make Marvel's portfolio of publications appear more attractive to prospective buyers. Then again, it's likely that negotiations with Perfect Film would have been rattling along from the early part of 1968, and that Goodman's comics mags had nothing to do with that.By 1971, Goodman was halfway out the door at Marvel, and with the success of Robert E. Howard's Conan character in the Marvel colour books and Stan's ascendency to Publisher, Marvel took another swing at the black-and-white mag market with the introduction of the slightly racy Savage Tales, cover dated May 1971.

Besides the cover-featured Conan the Barbarian, the mag also gave us an equally titillating Ka-Zar story by John Buscema, a post apocalypse macho fantasy Femizons drawn by John Romita, a "blaxploitation" story, Black Brother by Denny O'Neil and Gene Colan and the first appearance of Man Thing by Gerry Conway and Gray Morrow (coincidently on sale the same month as DC's House of Secrets 92, which debuted the character Swamp Thing, creation of Gerry Conway's then-roommate Len Wein). But still Marvel struggled with the format.

The second issue of Savage Tales (Oct 1973) wouldn't come along for another two-and-a-half years, featuring mainly Barry Smith's Conan and a few reprints. And by this time, Marvel had already launched Dracula Lives (Apr 1973), Monsters Unleashed (Jun 1973), Vampire Tales (Jul 1973) and Tales of the Zombie (Aug 1973) in an all-out assault on beachhead Warren ...

Next: The Best Marvel Annual

Nhận xét

Đăng nhận xét